9 March 1972 – American aircraft recorded their 100th protective reaction strike of the Vietnam War against enemy surface-to-air missile and antiaircraft artillery sites. (1)

“In late 1971 and early 1972, the United States was preparing to depart South Vietnam, but the North Vietnamese were not. They were concentrating forces and equipment near the Demilitarized Zone, preparing for what would shortly become known as the “Easter Offensive” of South Vietnam.

The North Vietnamese were also increasingly aggressive. Between November and February, more than 200 surface-to-air missiles were fired at US aircraft, compared to about 20 for the same interval a year before. The number of incursions by MiG fighters into South Vietnam and Laos increased by a factor of 15.”

After the end of the “Rolling Thunder” campaign in 1968, there had been no regular bombing of North Vietnam, although intensive reconnaissance

continued. In November 1968, less than a month after initiation of the bombing halt, the North Vietnamese shot down a reconnaissance aircraft. Fighter escorts were assigned and given “protective reaction” authority. They could attack any missile or anti-aircraft artillery sites that shot at them. The authority was later expanded to include MiG fighters and Fan Song radar sites when the fire-control radar was activated against reconnaissance aircraft or their escorts.

US airmen were saddled with extensive and restrictive rules of engagement that specified when and how they could attack the enemy. The rules kept changing, and they did not come in a neat list. They consisted of a compilation of wires, messages, and directives.”

On August 1, 1971, MGen William Lavelle arrived in Saigon as the commander of the 7th Air Force. In that capacity, “he had operational control of Air Force units based in both Vietnam and Thailand. He was also deputy commander for air operations for Military Assistance Command Vietnam or MACV. By that time, Vietnamization—the transfer of responsibility for the war to the South Vietnamese—was well along, and US forces were steadily withdrawing.”

During the months that Lavelle was commander of the 7th Air Force, the tight rules of engagement were frequently suspended for a “limited duration.” This happened, for example, when Washington officials wanted to send the enemy a message related to the negotiations.”

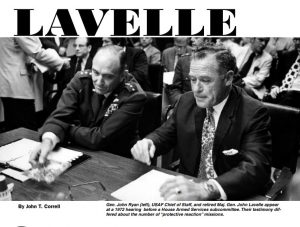

What happened next became fodder for an investigation into Lavelle’s use of protective reaction strikes. In 1972 during a House Armed Services subcommittee, Lavelle said that he “chose to make a very liberal interpretation” of the rules of engagement with these strikes as they were all preplanned with routes in and out, dive angles, aim points and other details worked out before the mission was launched. This made them less “reactive” and 7 months after Lavelle’s arrival in Saigon he was recalled to Washington originally for “medical reasons” but later revised to read “because of irregularities in the conduct of his command responsibilities”.

The Air Force said that in 28 documented instances, Lavelle had directed the unauthorized bombing of North Vietnam under the guise of “protective

reaction” strikes, exceeding his authority and in violation of the rules of engagement. Operational reports were then falsified to conceal the actual nature of the strikes.

Ironically, the North Vietnamese Army launched its Easter Invasion of South Vietnam on March 30, 1972, a week after Lavelle’s recall. The bombing of North Vietnam resumed, and the 7th Air Force was flying missions daily against the very kinds of targets that Lavelle had stretched the rules of engagement in order to attack.

For more of the story go to https://www.airforcemag.com/PDF/MagazineArchive/Documents/2006/November%202006/1106lavelle.pdf

Source: (1) Wikipedia; (2) https://www.airforcemag.com