Stationed at Bien Hoa, Hopkins was called off the alert with only minutes to get in the air to fly three close-air-support missions in one night to help U.S. Army Special Forces at a base along the Cambodian border. The troops were under heavy attack by the Viet Cong. “Usually they waited until they were in deep trouble” to call, Hopkins said. “I always wished they would have called for us earlier.”

On that night, “as each one of us finished [dropping our ordnance], the next set of fighters would come in to keep the pressure on the enemy,” Hopkins said of his most memorable experience in the Hun. By the time Hopkins went up for this third mission, “dawn was breaking, and the bad guys had broken off the attack because they prefer to fight at night. So they ran back across the Cambodian border.

“At that time during the war, we were not allowed—we, the American forces—were not allowed into Cambodia. That was a political decision and one of our rules of engagement.” The forward air controller told Hopkins and his wingman to return to base but pointed out the tin buildings that the enemy had fled to just a kilometer across the Cambodian border.

“By now I was physically and emotionally involved in this particular firefight that occurred all night long,” Hopkins said. “So out of frustration—there was nothing else we could do—we went back about 10 miles into South Vietnam, headed back for these corrugated tin huts…and just before the border we pulled up our nose and we jettisoned all of our ordinance toward those things. I have no idea if we hit ’em or not. Maybe we didn’t, probably didn’t, but it made me feel better anyway.”

Hopkins said that a few days later he was on desk duty when a Green Beret walked up to him. “He said, ‘Do you know any of the pilots that have been up there that night?’ I said, yeah, I was. He just said, ‘Thanks for saving,’” Hopkins said, stopping mid-sentence as his eyes filled with tears. Clearing his throat, he continued, “He said, ‘Well, thanks for saving my life.’”

That and another encounter, watching two soldiers come out of the jungle with scratches, welts, and mud-caked on their uniforms and boots to get a can of boned chicken from the base exchange at Bien Hoa, led to a turning point for Hopkins. “The sight of these guys all of a sudden put, put it into perspective, you know, who we were protecting when we were doing this close-air support, and it made a big difference.… After that, I never felt bad about risking my life to try and help those guys on the ground.”

According to Hopkins, F–100s flew more than 360,000 missions in Vietnam, most of them to provide close-air support to troops in the south. Missions involved multiple aircraft working together to aid troops and required precision that would be stressful even in peaceful settings. Forward air controllers talked to troops on the ground and flew at 2,000 feet to relay the location of the fight to other pilots, while Douglas C–47 Skytrains cruised at 10,000 feet to drop phosphorus flares that “put out 3 million candlepower of light” and white smoke to illuminate the target areas. F–100 pilots dove through the flares from 8,000 feet to just 50 or 100 feet above the ground at 450 knots with their lights off to avoid detection before dropping two cans of napalm and two 500- or 750-pound high-drag bombs, and firing four 20-mm revolver cannons with 200 rounds each. Meanwhile, intense firefights on the ground created “smoke and flames and things like that coming up to make it even more hazy.”

Precision bombing was essential on these missions, Hopkins stressed: “They ask us to come in and drop such dangerous stuff like napalm and bombs and strafe extremely close to these guys because the bad guys are literally climbing over the barbed wire trying to get inside of this compound to kill the Special Forces guys.” – Source AOPA “One More Time” by Alyssa J. Miller, Nov 1, 2016

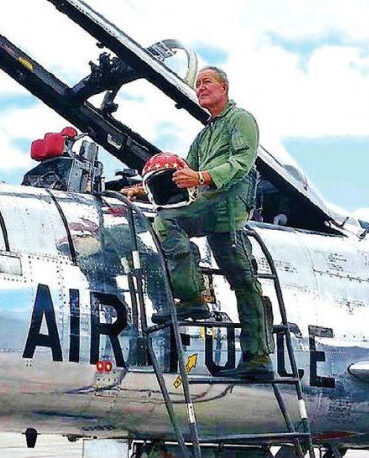

In 2016 “Hoppy” had the chance to fly an F-100 again. About that day he says, “I’m still on cloud nine because of my ride in the F-100 last September 19th. As I laid awake in bed this morning at about 0400 I suddenly realized why…… it’s that damned airplane. A supersonic, high-performance jet, beautiful in design, operational only about 10 years after WW II, still with WW II instruments that took off and landed almost twice as fast as any WW II fighter, was expected to be flown in all kinds of bad weather, over oceans, air refueling, in combat, dropping WW II ordnance, day or night, entertained and impressed millions of Thunderbird watchers, sat alert with nuclear bombs with a plan to deliver it at the top of an Immelmann and was flown by one shit hot guy who had unbelievable talent to perform all this. That airplane is what defines us as a very special bunch of men. That airplane is the glue that binds us together as the Super Sabre Society. We were and maybe still are the best fighter pilots the Air Force ever had.

We were the computer, the navigator, the engineer, the gunner, the bombardier, the guy with lightning-fast reflexes that made all the decisions, flew with overlapped wings to keep sight of lead from takeoff to landing, trusted each other with our lives, worked hard and played hard, had beautiful wives that loved us for better or worse and were the pride of the Air Force. This plane defines us as the best of our time and without it our lives and memories would be missing that electric feeling of pride that we feel when we think back of our days in the F-100. My ride reminded me of who we are and what we flew. We are the F-100 pilots. We were the best.” – Source: friendsofthesupersabre.org “Hoppy’s F-100 Flight”

Bob “Hoppy” Hopkins Caterpillar Story

F-111 ZION CRASH

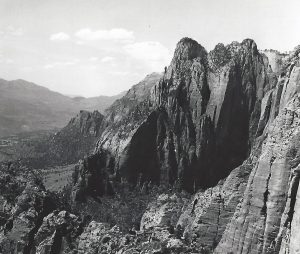

There’s a black smudge high up on the cliff above the visitor’s center in Zion National Park, Utah. That’s where my F-111 fighter-bomber impacted after I ejected from it in July 1973.

I was an instructor pilot at Nellis AFB in Las Vegas, Nevada, where my wingman and I had taken off on a training mission with two pilots who were learning to fly the F-111. They had completed ground school and simulator training, but this was their first ride in the Mach 2.5, 40-ton AARDVARK. After take-off, my wingman went to his designated training area and I went to mine. The weather was clear, and the terrain below was colored with red and white rock formations and cliffs. On this first ride, I was to demonstrate the aircraft’s flight characteristics by varying airspeed, lowering the landing gear, flaps, and slats, performing rolls and pulling the wings back. With the wings all the way back, the F-111 silhouette looks very much like a paper airplane.

I was an instructor pilot at Nellis AFB in Las Vegas, Nevada, where my wingman and I had taken off on a training mission with two pilots who were learning to fly the F-111. They had completed ground school and simulator training, but this was their first ride in the Mach 2.5, 40-ton AARDVARK. After take-off, my wingman went to his designated training area and I went to mine. The weather was clear, and the terrain below was colored with red and white rock formations and cliffs. On this first ride, I was to demonstrate the aircraft’s flight characteristics by varying airspeed, lowering the landing gear, flaps, and slats, performing rolls and pulling the wings back. With the wings all the way back, the F-111 silhouette looks very much like a paper airplane.

Everything was normal up to 25 minutes into the flight when I noticed that we were approaching the northern edge of our training area. I took the controls back from the other pilot, who had previously flown the F-4 Phantom in Vietnam. He was an experienced pilot but not in the F-111. I made a tight turn to head us back to the middle of our training area. Just as I rolled out of the turn, the windscreen in front of me broke into thousands of pieces the size of a thumbnail and raced toward me at 450 knots. Thank God I had my oxygen mask securely fastened and my visor down over my eyes, because without the protection they provided the pieces of glass would have taken the skin off my face. I’m sure it would have been fatal.

The buffeting from the wind blast increased as the glass canopy hatches blew out. All I could hear was the roar of the wind. Pieces of glass had flown between my mask and visor and were rolling around my eyelids. I remember pulling the control stick back to gain altitude — the maneuver pilots are taught to do if a bail-out is probable. I opened my eyes for a moment to see if I could get a visual glimpse of the aircraft’s attitude and find out what had happened.

In the brief time, I could keep my eyes open, I saw shards of metal ripping off the top of the instrument panel and coming at me at neck level. This was the final straw in making my decision to eject. With my eyes closed, I reached for the yellow ejection handle, pulled, and squeezed. Nothing happened –for 1/4, second, that is. Then I began the ultimate ride of my life.

The F-111 has a unique ejection system — the entire cockpit explodes away from the airplane and then a 25,000-pound thrust rocket engine ignites under the seat to lift the cockpit or escape capsule, as it’s called, away from the airplane. Once the capsule is clear, a 70-foot diameter parachute deploys and the pilot floats down, still in the seat with the instruments and radar scope, etc… but they were not connected to anything. The capsule is about the size of a VW Beetle and weighs over 2,000 pounds.

The ejection went perfectly. The rocket ignited and felt more like a hard push than a kick in the seat. The noise from the wind blast and rocket was deafening. My eyes were closed until I felt the capsule decelerating and heard the parachute make a gentle popping sound as it fully blossomed. When I opened my eyes, the first thing I saw was the F-111 crashing into a cliff approximately 5,000 feet below.

I thought immediately about the loss of a $13-million airplane I was responsible for, and I was aware of the thorough questioning I would go through if I survived the day. I next looked to my left and asked the other pilot if he was okay. He said, ” I’m O.K., but we’re in deep trouble now.” I thought he was worried about the loss of the airplane, so I tried to calm him down by saying, “Don’t worry about the F-111. You’re in student status today, so if anybody gets in trouble for losing the airplane, it will be me.” He replied, “I don’t give a damn about the airplane, look below us.” I leaned out of the capsule, and for the first time, I saw the majestic rock formations of Zion National Park. It had deep canyons with rugged and colorful mesas. I relaxed a bit after seeing the gorgeous views and knowing that we had just survived a major accident and ejection. Suddenly I came to my senses; we had another emergency to endure. We were going to land among all these mesas and canyons.

Descending in an individual parachute, a person can steer the chute away from dangerous landing sites. We, however, could not. I imagined that the capsule would hit the edge of one of these massive rock formations and spill the air out of the parachute and we would fall the last 1,000 feet or so to the canyon floor. There was nothing we could do but wait and I began thinking this was the end. In Vietnam, I had flown 303 combat missions in the F-100 fighter-bomber and my aircraft had been hit by ground fire numerous times. During the 1968 TET Offensive, my base was partially overrun by the North Vietnamese. Another time I had to land an F-100 without a nose landing gear and only a minute or two of fuel left. Through all of these things and a few others, I never thought I was going to die, but floating down in that capsule I just knew it was all over.

Descending in an individual parachute, a person can steer the chute away from dangerous landing sites. We, however, could not. I imagined that the capsule would hit the edge of one of these massive rock formations and spill the air out of the parachute and we would fall the last 1,000 feet or so to the canyon floor. There was nothing we could do but wait and I began thinking this was the end. In Vietnam, I had flown 303 combat missions in the F-100 fighter-bomber and my aircraft had been hit by ground fire numerous times. During the 1968 TET Offensive, my base was partially overrun by the North Vietnamese. Another time I had to land an F-100 without a nose landing gear and only a minute or two of fuel left. Through all of these things and a few others, I never thought I was going to die, but floating down in that capsule I just knew it was all over.

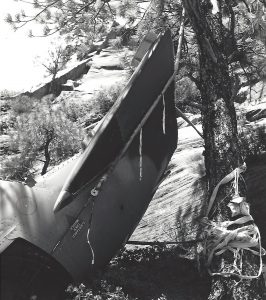

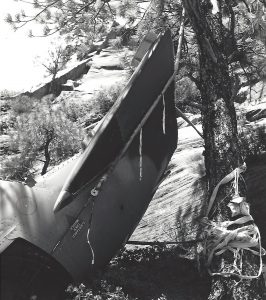

We finally hit. The impact was not severe but we immediately started to roll down a very steep, rocky slope. We were hunkered down inside our capsule and protected over our heads by a sort of roll bar. The capsule tumbled over and over and finally came to rest — upside down. The parachute was dragging behind us and had caught on something. Just then we heard a loud crack, and we started rolling down an embankment again. Finally, the capsule caught in something that held us and we climbed out.

The capsule was lying on its side with the spent rocket engine still smoking. Less than three or four minutes prior, we had been flying a normal mission, and now we were in a small lightly wooded canyon. The only sound was that of a nearby stream and some birds chirping about the invasion of their territory. We checked ourselves and then each other for injuries. Except for some minor cuts from the glass we were okay.

Soon my wingman in the other F-111 was circling overhead. We got out the survival emergency radio and called for assistance. About two hours later, a helicopter picked us up and took us back to Nellis AFB in Las Vegas, Nevada. My wife, Gladie, had been informed of the accident by my squadron commander in such a way that she never thought I was not okay. He called her on the phone and started with, “Hoppy will be a little late tonight because he’s got to walk home.” Then he continued on about the ejection part and sent the operations officer and his wife with a bottle of my favorite scotch to our house to be with Gladie until I got home.

A few days later the capsule was recovered and feathers were found jammed in the spot where the windscreen had been fastened to the plane. The feathers were sent to the Smithsonian Institute where it was determined they were from a White-Throated Swift – a bird whose average weight is 1 1/4 oz!!

My Plane was the fourth F-111 to be lost due to bird strikes. The plane was designed to be flown at high speeds of 600 knots or more, at altitudes of 200 to 500 feet. This is also the altitude at which most birds like to fly. As a result of my accident, a new thicker windscreen was installed on every F-111. Since my accident occurred there was never another F-111 lost due to a bird strike.