Bud Day was born on February 24, 1925. He dropped out of high school in 1942 to join the Marine Corps where he spent thirty months overseas in the Pacific Theatre, leaving active service in 1945. He joined the Army Reserve, acquired a Juris Doctor from the University of South Dakota in 1949, and a BS and Doctor of Humane Letters from Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa.

The “smartest move of my life”, says Bud was his marrying Doris Marlene Sorensen in 1949. Bud was recalled by the USAF as a Second Lieutenant in 1951 and he attended jet pilot training followed by two tours in Korea and four years flying fighters in England (He made Air Force history with the first no-chute bailout from an F-84-F in 1957!)

The Days adopted their first son, Steven, and were soon reassigned as Commandant of Cadets, St. Louis University, Missouri. Bud acquired a Master of Arts in political science. They adopted a second son, George E. Jr., in 1963 and the family spent three years in Niagara Falls, N.Y., where Colonel Day flew fighters. The family was increased by twin adopted girls, Sandra M., and Sonja M., just before Bud was assigned to fly an F-100 fighter bomber in South Vietnam. After seventy-two missions, he was reassigned as Commander of MISTY, the first jet FAC unit flying in North Vietnam. He was shot down on the sixty-seventh mission while striking a missile site. During ejection, he had three breaks in his right arm and a dislocated left knee.

Colonel Day was the Commander of several Vietnamese prisons, the Zoo, Heartbreak Hotel, Skidrow, and Misty and Eagle Squadrons. He was incarcerated for sixty-seven months and executed the only successful escape from North Vietnam into the South. He was recaptured near Quang Tri City, South Vietnam, after about two weeks of freedom. He was shot in the left leg and hand and had shrapnel wounds in his right leg. For this, he was heavily tortured, since he was labeled as having a “bad attitude.” He was “hung”, his arms were broken and paralyzed.

As Commander of the Barn in the Zoo, he was the last of the “Old Heads” tortured – a four-month stretch in irons, solo, and massive beatings with the fan belt and “rope”. Of six, he was one of three who survived from Heartbreak Hotel in 1970.

Asked many times what sustained Americans in this environment, Colonel Day answers: “I am, and have been all my life, a loyal American. I have faith in my country and am secure in the knowledge that my country is a good nation, responsible to the people of the United States and responsible to the world community of nations. I believed in my wife and children and rested secure in the knowledge that they backed both me and my country. I believe in God and that he will guide me and my country in paths of honorable conduct. I believe in the Code of Conduct of the U.S. fighting man. I believe the most important thing in my life was to return from North Vietnam with honor, not just to return. If I could not return with my honor, I did not care to return at all. I believe that in being loyal to my country that my country will be loyal to me. My support of our noble objectives will make the world a better place in which to live.”

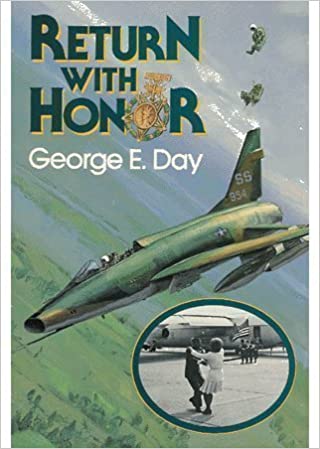

Note: Colonel Day has written a book telling of his experiences in more detail. It is entitled, “Return with Honor.”

Colonel Day’s decorations include our nation’s highest – the Medal of Honor, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Air Medal, Purple Heart, POW Medal, and other Vietnam service awards and medals. He has numerous awards and medals from his service prior to Vietnam.

His family resides in Glendale, Arizona. His wife was intensely active in POW/MIA affairs and was chosen TAC wife of the year as well as receiving other honors for service to the POW-MIA cause.

Source: https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/d/d051.htm

George E. “Bud” Day Headed West on July 27, 2013

George E. “Bud” Day Headed West on July 27, 2013

Retired Col. George “Bud” Day, a Medal of Honor recipient who spent 5½ years as a POW in Vietnam and was Arizona Sen. John McCain’s cellmate, has died at the age of 88, his widow said Sunday.

Day, one of the nation’s most highly decorated servicemen since Gen. Douglas MacArthur and later a tireless advocate for veterans’ rights, died Saturday surrounded by family at his home in Shalimar, after a long illness, Doris Day said.

“He would have died in my arms if I could have picked him up,” she said.

Day received the Medal of Honor for escaping his captors for 10 days after the aircraft he was piloting was shot down over North Vietnam. In all, he earned more than 70 medals during service in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

He was an enlisted Marine serving in the Pacific during World War II and an Air Force pilot in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

In Vietnam, he was McCain’s cellmate at one camp known as the Plantation and later in the infamous Hanoi Hilton, where he was often the highest-ranking captive. During his imprisonment, the once-muscular, 5-foot-9 Day was hung by his arms for days, tearing them from their sockets. He was freed in 1973 — a skeletal figure of the once dashing fighter pilot. His hands and arms never functioned properly again.

Source: http://lisbonreporter.blogspot.com/2013/07/sadly-we-report-passing-of-colonel.html

GEORGE E. “BUD” DAY

GEORGE E. “BUD” DAY

Colonel – United States Air Force

Shot Down: August 26, 1967

Released: March 14, 1973

Day was the forward Air Control Pilot in the F-100F on a strike mission over a missile site near the DMZ when he was hit. B-52s were bombing along the southern edge of the DMZ. He started a pass coming in from the southeast to the northwest. He was doing about five hundred and was full of fuel when the plane was hit in the aft section.

The GIB (guy in front) was on his first mission. The sequence for ejection was that the back seat had to go first. Day fired the canopy and punched out. The GIB followed almost immediately and landed about a mile and half away, a little south, between twenty-five and forty miles north of the DMZ. A rescue helicopter picked him up as the Vietcong got to Day. By the time the helicopter attempted Day’s rescue, the Vietcong had stripped Day and had moved about a quarter-mile.

In the ejection, Day’s left arm was broken in three places, twice in the forearm and once in the upper arm. He was blinded in the left eye for a long time due to a blood clot or a bruise. His left knee was dislocated, as he hit the ground unconscious.

The militia group that captured Day were undisciplined, untrained “kids” between sixteen and twenty years old. That did not prevent them from establishing a brutal torture regimen. Day recalls, “They would tie up my feet with about twenty-five feet of a cotton clothesline rope. It was one of the funniest things you ever saw. They would wrap it around my legs about twenty times and then tie up to sixty granny knots in the rope. Damndest exercise I had ever seen. It was really kind of funny. After they stopped tying my hand to the ceiling, I started practicing and after a while, I could untie the whole strand of rope around my feet in twenty or thirty minutes – it was a piece of cake.”

Early in his captivity he was able to escape. At the time, Major Day was about forty miles north of the DMZ, and from visual sightings during previous flights, he believed that the region consisted entirely of rice paddies all the way down to the DMZ.

However, four or five miles south of the camp, the paddies changed to hard, cleared land. After traversing the rice paddies, Day continued for about ten miles until he hit an area of light forestation at dawn. After making about twenty miles that first night, he stopped to rest near a North Vietnamese artillery position that was firing.

After staying awake for more than 24 hours, Day lost all reference to the sky in a cloudy mist. He slid under some bushes and went to sleep. After it stopped raining, “something landed very close to me, and I took a hit in the leg. The concussion picked me up off the ground and then crunch back down. My sinuses and eardrums were ruptured and I was really nauseated. I barfed and barfed and barfed and barfed until I thought I’d barfed my kidneys out. I lost my equilibrium and couldn’t even stand up. I was bleeding out of the nose and some of the vomit was bloody. A couple days later when I felt better I took off and was walking fairly well although my leg began to swell because of the shrapnel I’d taken in it.

That day I lost about a mile because I started walking in circles. Somewhere about the tenth day I started running out of control. I began to hallucinate and talk out loud. I didn’t realize what happens after you starve yourself. It would frighten me to hear myself talking out loud and the hallucinations were just wild.”

The hallucinations drove Day right into the path of the Vietcong. He tried to take off running, but after the fourth or fifth step, they started firing. He was hit in the leg and hand, but he continued down the trail for about thirty feet before veering off and passing out. He was unconscious somewhere between eleven and fifteen days. They took him back to the same camp he had escaped from, with the trip lasting thirty-seven hours.

That October he had the first interrogator who spoke English. Day could barely understand him – but the brutality from him was loud and clear. The arm that had partly healed, was broken again.

“They had hung me up from the ceiling and paralyzed this [left] hand for about a year and a half. I could barely move my right hand. My wrist curled up and my fingers were curling. I could just barely move my [right] thumb and forefinger.”

“In some of the torture sessions, they were trying to make you surrender. The name of the game was to take as much brutality as you could until you got to the point that you could hardly control yourself and then surrender. The next day they’d start all over again.”

“I knew what he was – he was obviously Cuban and had either been raised at or near the U.S. Naval base at Guantanamo. He knew every piece of American slang and every bit of American vulgarity, and he knew how to use them perfectly. He knew Americans and understood Americans. He was the only one in Hanoi who did.

“I had gotten to the Zoo on April 30, 1968, and he had already pounded Earl Cobiel out of his senses. No one knows exactly what happened. A young gook, whose name escapes me, and two other beaters beat him all night. They brought him out after a fourteen or fifteen-hour session, and he obviously didn’t have a clue as to what was going on. He was totally bewildered and he never came unbewildered.

“The gooks kept thinking he was putting on, so they would keep torturing him. The crowning blow came when one of the guards some people called Goose struck him across the face with a fan belt under his eye, and the eyeball popped out.

“The guy never flinched, and that was the first time the gooks finally got the picture that maybe they’d scrambled his brains.

“It sounds so savage you have trouble picturing it.”

SOURCE: WE CAME HOME copyright 1977, https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/d/d051.htm