40 years later: former Charleston Airman, Vietnam POW looks back, article by Airman 1st Class Tom Brading, Joint Base Charleston Public Affairs / Published March 28, 2013

JOINT BASE CHARLESTON, S.C. — Forty years have passed since the United States ended its involvement in the Vietnam War, and forty years have passed since many of its sons who engaged in the war and were captured by the enemy, were liberated and returned home.

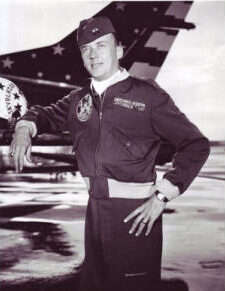

One of those liberated prisoners was retired Col. Will Gideon, former 437th Airlift Wing Supply Squadron commander, who was a pilot with the 67th Tactical Fighter Squadron the day he was shot down and captured by the North Vietnamese August 7, 1966.

Gideon, a native of Arlington, Va., flew 54 successful missions into Vietnam before being shot down.

“We came into the mountains low that day,” said Gideon, in regards to the aircraft formation. “After I released my bombs, I rolled the jet to its side and popped back up. It started like any other mission … only, I had no idea it would be my last (mission as a pilot.)”

From within the cockpit of his jet, Gideon witnessed a fiery explosion in the atmosphere igniting from another F-105 directly in front of him. The aircraft’s pilot safely ejected, but was captured by the deceptive enemy below. In a flash, black smoke filled the red sky and cloaked Gideon’s sight, blinding him nearly instantly. Bullets cut through the air, whizzing as they buzzed all around. Gideon remained calm, but could only hear the sound of his heart beating and ground fire that was coming from North Vietnamese soldiers, hidden within the foliage of the jungle below.

“I tried like hell to get out of there,” said Gideon. “This is when everything started happening really fast.”

And, going fast was on Gideon’s side. He was piloting an F-105, the Air Force’s premiere jet fighter at the time, and it was able to reach supersonic speeds quickly. However, his distance to the ground was against him.

According to Gideon, he knew he was in trouble when he felt a jarring explosion, as well as the ratatatat of bullets bouncing off his jet. Before he could evade the enemy attack, the aircraft began shaking and spiraling downward uncontrollably.

“It was like someone grabbed the tail end of the plane and wouldn’t let go,” said Gideon. “The jet was spinning out of control. It was all happening so fast, but I remember starting to see everything go grey and feeling numb.”

Accepting his fate, Gideon knew his plane was destined to crash into the Vietnamese mountainside. With every passing moment, more control was slipping through his fingers. Knowing he was also about to pass out, Gideon was losing control of more than his jet, but also himself.

“My life wasn’t flashing before my eyes,” said Gideon. “My training was. I knew what I had to do to survive … death wasn’t an option that day.”

Through the disarray of being shot out of the sky, he thought back to his pilot training at Nellis AFB, Nev., and managed to eject. From there, everything went blank.

Gideon awoke in darkness, unclear of the amount of time that had passed or where he was. He was nowhere near the crash site. He was stripped of his clothes, in pain and locked inside a small, humid jail cell. The only light piercing the eroded room was coming from a barred window.

“I was out for nearly a week,” said Gideon. “When I finally woke up, my left leg was in a cast below the knee. I can’t recall exactly when it was broken. My shoulder and head were swollen and I could barely move.”

Due to his memory loss, Gideon wasn’t sure how or when he had incurred his injuries. However, it was common for American POW pilots to enter a detention camps hurt due to injuries sustained while ejecting from their aircraft.

A total of 13 facilities in North Vietnam were used as detention camps for American POWs; five camps were located in Hanoi and the rest were outside of the city. With the exception of the Hỏa Lò Prison, sarcastically named the Hanoi Hilton by American POWs, the official names of the 12 other Vietnamese camps were unknown.

Gideon’s camp was like other countryside camps used by the enemy, the sound of the creek and wildlife echoed through the surrounding canopy of coconut palm and banana trees. The seemingly peaceful Vietnamese swamplands were a smoke and mirrors to its reality. Rice paddies were being tended by North Vietnamese civilians. It was a lonely place, undisturbed by the rest of the world. Although Gideon didn’t know where he was, he would be a prisoner there for roughly six years, seven months and 13 days.

“The captures thought I was really screwed up mentally,” said Gideon. “I refused to wear the prison rags they provided, I didn’t touch my food and for the most part, I had no idea where I was. This behavior went on for weeks.”

A young Navy officer from Florida, known simply as Lt. Browning, was Gideon’s cell mate when he arrived at the prison. Browning helped Gideon adjust to his new surroundings by tending to his new friend’s injuries, explaining where Gideon was and even refusing to eat Gideon’s food portions.

“Browning wouldn’t eat my food even though I refused to touch it, and not because he wasn’t hungry or afraid of being punished,” said Gideon. “He was starving and easily could’ve eaten it, but he didn’t want the capturers to think I was eating. He wanted them to know how sick I was. He was just doing it because it was the right thing to do.”

The integrity displayed by his cell mate helped Gideon transition to his new, dire surroundings. One day, Gideon finally accepted a bowl of rice. Within minutes, the entire bowl was gone. A rare humble display of humanity was shown by the prison guard, who noticed Gideon quickly eat his rice and offered him a second bowl.

However, the display of humanity was short lived.

Gideon, like most American POWs at the time, was often isolated from the other prisoners during questioning. Bound by his wrist with rope, he was viciously interrogated by North Vietnamese soldiers. But, he did not falter, nor did he break. With a body battered from the savage conditions and even after witnessing the pain, and broken bodies, of his fellow service members; Gideon never reached his breaking point.

“Selling out my country wasn’t an option,” said Gideon, remaining true to his commitment as an Airman. “They knew I wasn’t saying a word, other than what I was trained to say.”

American POWs were often forced to sign confessions of guilt, write letters to American politicians or be manipulated in other ways, and used as an asset for the North Vietnamese military agenda. Some prisoners were given special treatment, or favors by their capturers, by simply cooperating with them. Gideon refused any special treatment because he felt to accept anything from the enemy would place him in the enemy’s debt, a price he refused to pay.

“There were times I started to become discouraged,” said Gideon, looking back on his tested resiliency as a POW. “Every year that passed, [away from family] I wondered what was happening back home. New prisoners would come in and say things like, ‘there’s no way we’ll be here after the first of next year’ and that year would pass. Then another year passed and another and so on … and eventually, many years passed. At times, that was very discouraging.”

Although he could have easily succumbed to the despair, Gideon never gave up on his faith in the United States. Years passed, and his family waited patiently for his return. He knew they would be taken care of by the Air Force until that day arrived.

“There was no escaping the prison,” said Gideon. “Even if there were, I couldn’t leave those men behind. I wouldn’t be able to live with myself knowing the punishment that would have been bestowed upon them.”

In the years Gideon was prisoner, only one prison break was attempted. The two Americans that attempted the escape were caught within hours and subjected to even longer amounts of torture than they spent away from the prison. One of the men died from the excessive beating he received from the enemy.

Gideon never gave up, through more than six years of prayer, exercising in his prison cell, believing on the United States’ promise to bring him home and being friends with his fellow American POWs, he kept hope alive. And although Comprehensive Airman Fitness didn’t exist during the Vietnam War, Gideon and his fellow prisoners unknowingly used those pillars to survive.

On March 4, 1973, Gideon’s prayers were answered. He was liberated and able to return home. Looking back, he holds no grudge against his capturers, and his positive outlook on life has helped him move on from the turmoil that shackled him physically and mentally for the better part of a decade.

Gideon went on to retire from the Air Force as a colonel and spent his last years of active duty commanding the 437th AW Supply Squadron and Resource Management deputy commander at Charleston Air Force Base, S.C. Upon retirement, he remained in the local area and today lives a quiet life in Mount Pleasant, S.C.

Even though he has moved on with his life and let go of the pains of yesterday and rarely talks about his time as a POW, he will never forget the sacrifices made and encourages everyone to remember the 1,655 still missing after the conflicts in Southeast Asia more than 40 years ago.

To read a wonderful story about Willard Gideon’s POW bracelet go to: https://www.thestate.com/news/local/military/article27750580.html

Willard Selleck Gideon, Col USAF (Ret), “Headed West” on October 10, 2016,

Willard Selleck Gideon, Col USAF (Ret), “Headed West” on October 10, 2016,

Col. Willard Selleck Gideon, a retired deputy commander of resource management for the 437th Airlift Wing at the Charleston Air Force Base, a Vietnam prisoner of war died Oct. 10, 2016. He was 85.

Gideon joined the Air Force in 1952, launching his military career and earning his pilot wings in 1954.

After a tour in Europe, Gideon became an instructor pilot at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas until 1965, when he was transferred to North Vietnam to fly combat missions during the war. While flying his 55th mission, he was shot down and taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese. He was held captive for 2,402 days, almost 7 years.

After being freed during Operation Homecoming, he attended the University of Nebraska and then worked at the Charleston Air Force Base until his retirement in 1983.

He leaves behind two children, three stepchildren, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

WILLARD SELLECK GIDEON

WILLARD SELLECK GIDEON

Rank/Branch: Lieutenant Colonel, United States Air Force

Date of Birth: 03 June 1931 Takoma Park MD

Home City of Record: Arlington VA

Date of Loss: 07 August 1966

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 212000 North 1063200 East

Status (in 1973): Returnee

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F105D #1758

Missions: 55

“Born June 3, 1931, in Takoma Park, Maryland. Graduated from Washington and

Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia in 1949. Graduated from Butler Prep School in Silver Springs, Maryland in 1950. I joined the Air Force in February 1952 and entered Aviation Cadets in January 1953. Graduated in March 1954 from Williams AFB, Arizona.

I flew 55 missions in North Vietnam from both Korat and Takhli. I was shot down on 7 August 1966 about 25 miles northeast of Hanoi flying an F-105D. I have spent my entire career flying fighters in the States, Europe and the Far East.

The fighter business has always held the most interest for me and I hope to continue in this branch of flying after completing the Air War College in May 1974.

It is wonderful, beyond description, to be back in this great nation of ours once again. My eternal gratitude is with all of you who have supported the POW/MIA program.”

Willard Gideon retired from the United States Air Force as a Colonel. He and his wife Jeannine resided in South Carolina. He passed away in October of 2016.

Source: Compiled by P.O.W. NETWORK from one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. 2016

Source: WE CAME HOME copyright 1977; Captain and Mrs. Frederic A Wyatt (USNR Ret), Barbara Powers Wyatt, Editor P.O.W. Publications, 10250 Moorpark St., Toluca Lake, CA 91602 Text is reproduced as found in the original publication (including date and spelling errors).