Captain Allen T. Lamb, Jr., won the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism while participating in aerial flight as a Tactical Fighter Pilot over North Vietnam on 22 December 1965.

On that date, Captain Lamb participated in a strike on an SA-2 missile site on the Red River approximately fifty miles northwest of Hanoi, North Vietnam.

Despite accurate anti-aircraft fire and the knowledge that another SA-2 missile site was in the immediate area, Captain Lamb repeatedly made strafing passes at hazardously low altitudes to assure the destruction of the target. Through excellent teamwork and superb airmanship, Captain Lamb was able to find and destroy an SA-2 missile site that was not previously known to exist.

(source: https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/43017)

TRIBUTE TO LIEUTENANT COLONEL ALLEN LAMB

Mr. TILLIS. Mr. President, I rise today to pay tribute to Lt. Col. Allen Lamb, a retired Air Force pilot from the great State of North Carolina, for his many years of service to his country as a combat pilot and the important role he played in the development of U.S. Air Force tactics.

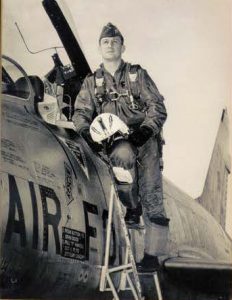

Lt. Col. Allen Lamb selflessly dedicated 20 years of his life to serving his country in the United States Air Force. During his service, he saw combat during both the Korean war and Vietnam war, while piloting a variety of aircraft from propeller-driven heavy bombers to the most advanced jet fighters of the era. Lieutenant Colonel Lamb had an uncanny ability of surviving the mid-air accidents that occurred on a few of the many combat and training missions that he participated in, and he is notable for successfully ejecting from four-engine, three-engine, and two-engine airplanes at different points during his career.

From protecting his B-26 bomber as a tail gunner from Soviet MIG pilots over Korea, to being distinguished as the first American pilot to successfully destroy North Vietnamese surface to air missile-SAM-sites in an F-100 Super Sabre fighter jet, Lieutenant Colonel Lamb’s Cold War service consisted of many hazardous and diverse assignments.

Although it is difficult to narrow all of the spectacular and death-defying accomplishments of Lieutenant Colonel Lamb’s career down to one specific achievement, his participation in the first “Wild Weasel” strike against a North Vietnamese SA-2 SAM site is particularly notable for the significant influence it had on future Air Force tactics.

In 1965, early in the Vietnam War, the U.S. Air Force was losing a considerable number of planes during the strategic bombing campaign in North Vietnam due to the effectiveness of deadly Soviet-supplied SA-2 SAMs that were strategically scattered throughout the country. As a result, the Air Force developed a daring solution to counter the SAM threat that involved using agile F-100 Super Sabre and F-4 Phantom fighter jets to detect and suppress the missile launching sites. The innovative Air Force mission” was soon given the name “Wild Weasel” because the anti-SAM mission was reminiscent of the way a hunting ferret enters the den of its prey to kill it.

In late 1965, Lieutenant Colonel Lamb was given command of leading the first Wild Weasel mission, Wild Weasel I. On this mission, which took place just over 50 kilometers from the North Vietnamese capital Hanoi, Lieutenant Colonel Lamb and his navigator Jack Donovan flew extremely low on multiple strafing runs and were successful in destroying a SA-2 SAM site that was not previously known to exist. Both men were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by the Air Force for their efforts.

Lieutenant Colonel Lamb respectfully declined receiving the Silver Star award when he was offered it because his crewman Jack Donovan was not also included. Wild Weasel I demonstrated that the Wild Weasel project was an effective method of identifying and eliminating enemy SAM capabilities, and it was essential in saving the lives of American bomber pilots as they continued to conduct missions over North Vietnam until 1973. Lieutenant Colonel Lamb completed the first, second, and third Wild Weasel kills during the war, and the tactics he was instrumental in developing during the Wild Weasel missions are

still utilized in modern Air Force operations to suppress enemy air defenses.

As a U.S. Senator, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and a North Carolinian, I am pleased to recognize and honor Lt. Col. Allen Lamb for his impressive career of military service, his critical role in the development of U.S. Air Force tactics, and his steadfast commitment to our country.

Allen Lamb – Caterpillar Club

March 28, 1963, was going to be a busy day for Allen Lamb. First, the young captain had a night tanker mission, acting as an IP for some general’s landing currency. The next morning he needed to be on the road to Fort Bragg rather early. At 0800, he was to begin jump school with the airborne grunts.

He hustled around his bird, eying the time anxiously. With the general in the flight, it wouldn’t do to be late. Once his engine rumbled to life, he completed his after start checks, then glanced around the ramp at Myrtle Beach as the din of six idling Super Sabres flooded the senses of those in the area.

He would be one of the two IPs in the flight. In case one IP aborted, the general needed a backup or he, too, would have to abort. “Actually,” Lamb thought with a chuckle, “with an IP in the back of the general’s ‘F,’ we have about 33 percent instructor pilots in this gaggle. Could be dangerous.”

It was just about dusk as the first element rolled. Lamb noted the time. They should be right on schedule for the tanker.

Lined up on the runway as the last element, he glanced at his young wingman, just back from Hun school and raring to go. They went through the usual signals for run-up and released brakes. The Huns jumped to life as the afterburners kicked in. Once airborne, cleaned up, and out of burner, they closed on the flight of four ahead.

The join-up was smooth and quick. Five and Six were tucked in trail as the main flight approached the cloud deck in fingertip. Once on top, Five and Six would move to the left wing for the short flight to the tanker track.

Lead radioed a channel change to Approach Control, and all six acknowledged. That would be the last transmission Allen Lamb was to hear that night. Nothing seemed to work with his radio, so he concentrated on flying smooth trail formation; his new wingman would need all the breaks he could give him.

At about 20 thousand feet in the climb, they broke out beneath a darkening sky. As per the briefing, Lamb began a slow move out to the left wing position. As he pulled up on the wing, he glanced over at Six, only to see him wobbling a bit and beginning to move forward after initially slipping a bit behind.

Positioned between the Hun off to his right and his wingman, Lamb held a nice, steady number Five position.

But on his left wing, things weren’t going all that well for number Six. As Lamb added power to move forward on the wing, Six felt himself sliding back and added a gob of power.

Too much power, the young pilot realized as he slid past his leader. Reducing power he suddenly remembered his navigation lights. He was supposed to have gone “brightflash” on them. Already, things were piling up pretty high on the inexperienced pilot. As he looked in the cockpit to go “bright-flash” on the lights, he suddenly realized he’d reduced power way too much. He was rapidly sliding back into number Five!

Allen Lamb was looking back at the lead four-ship when Six hit him. The right rear horizontal slab of number Six’s plane smashed into his cockpit area, bending lots of sheet metal and jamming the throttle at about 97% power. The impact also jammed the left console into the ejection seat handle.

As Six tumbled out of control, the pilot ejected into the darkened skies. All Lamb knew was that there had been a loud crash, then his stick and throttle froze! He was out of control, spiraling down into the blackness. Looking back over his head he could see lights on the ground. “Probably Columbia (South Carolina),” he thought.

He attempted to raise the ejection handles, but, jammed from the collision, they would not come up. He was trapped in the wildly plummeting airplane.

Desperately, he unstrapped from the lap belt and shoulder harness, blew the canopy, and attempted to crawl out of the cockpit with his chute and survival kit, but the windblast pinned him in the cockpit, snapping his head back violently, and preventing him from leaping over the side.

Really in trouble now, he clawed frantically, pulling himself back into the seat. Still, he could not raise the ejection handles or locate either trigger. Again, he attempted to stand, and, once more, the severe windblast pinned him in the cockpit. This time, as he clawed his way back into the cockpit, he must have jostled the ejection handles in such a way that the right handle finally deployed…exposing the trigger.

The last time he saw the airspeed indicator, the needle was pointing somewhere between 1.0 and 1.1 mach.

He was supersonic!

This time, he frantically grabbed at the ejection seat and found the right trigger exposed…which he pulled with all his might as he forced his head back and assumed the best ejection position he could manage. (To this day he has no idea where his left arm was as he pulled the trigger.)

The seat fired with Lamb unstrapped, causing him to roll backward over the seat as he and it cleared the plane and hit the brick-wall-like wind blast. With no idea how high he was, he clawed for the D-ring and pulled it with a mighty yank, realizing he was head down as the chute streamed out between his legs. The opening shock hit him like a sledgehammer, jerking him upright as he swung wildly under the canopy. He saw at least two panels missing, but otherwise, the chute seemed okay.

He realized his mask was still attached and found it filled with liquid as he unsnapped it. His blood! Looking around, all he could see was a milky darkness below. “Could it be water?” he thought and removed his helmet after deploying the underarm life preservers. He threw the helmet. “Thousand one, thousand two…” And he heard a splash. He was over water! And very low.

At that moment, he realized his survival kit was gone…probably ripped away during the ejection. Then, he hit the water. Instantly, he felt the cold and the chute’s canopy settled over him. His water survival training probably saved his life. He’d been through this very scenario at the PACAF Water Survival School and began carefully threading his way to the edge of the canopy. “Thank god,” he thought, “The folks at Myrtle Beach still wore LPUs, or I would have been a goner at this point without the survival kit.”

As he cleared himself of the heavy fabric, he was still entangled in shroud lines. Putting the shroud cutter to good use, he cut himself free of the heavy lines and canopy and distanced himself from the slowly sinking parachute.

Then, he had time to look around. Nothing. It was a very dark night. He could see nothing.

All Lamb knew was that he was in a fairly large body of water. He saw nothing. Nor could he hear the slightest sound. He was utterly alone.

His wingman, meanwhile, had successfully ejected from his tumbling bird and went through a fairly normal chute opening, descent and landing. He came down in knee-deep water in the very same lake as his leader. Spying a structure nearby, he found two men working on a lakeside cabin they were remodeling. Their fireplace was a godsend.

When he explained that one of his flight members may well have also ejected and was probably in the lake somewhere, they produced a phone. He called the base to alert them of the accident, and the two cabin workers promptly launched in their motorboat to search for Allen Lamb. Their search tactic was simple. They would turn off the motor periodically, yell like hell for “Captain Lamb,” and then listen for a reply. It was a big lake, and they repeated this drill for hours. But they didn’t give up….

Meanwhile, back in the flight, number Three had seen the collision and called out, “Lead, Six just ran into Five!” Lead’s immediate “Mayday” call initiated a massive Air Force search and rescue effort. For Allen Lamb, help was on the way…but from an unexpected quarter.

Lake Murray, northwest of Columbia, S.C., is a very large freshwater lake, stretching some 25 miles along the main length of the lake itself. A lot of water for two folks in a motorboat to search.

But there, in Lake Murray, March’s cold waters began to gnaw at Lamb. He sang out loud to keep himself warm. At one point, he’d considered removing his g-suit as a weight-saving measure but thought better of it because the g-suit provided considerable protection from the frigid water.

In the distance, he heard helicopters…searching for him, he hoped. Then, he realized he had absolutely no signaling devices on him!

Hours went by, and Lamb began to feel the effects of hypothermia. His shivering got worse, and the numbness in his fingers became extreme. He knew from his survival training that he was approaching a serious degree of exposure. He didn’t know just how long he could last but kept singing and moving his arms and legs to stimulate what warmth he could generate. His situation was growing tense, as hour after freezing hour, he floated helplessly in the LPUs.

Then, miracle of all miracles, he heard voices yelling, “Captain Lamb, Captain Lamb!”

As he yelled in response, he quietly cursed the 9th Air Force Stan/Eval folks for requiring the aircrews to remove their emergency flares—“for safety reasons,” they said. Now, he floated in a huge lake with no signaling devices of any kind: his flashlight had been ripped away in the ejection, and he had no flares hidden in his g-suit (as so many of the other guys were doing in defiance of the 9th AF Stan/Eval mandates).

Eventually, though, the cabin worker rescuers finally heard “Captain Lamb’s” weak replies and homed in on him in the darkness. They pulled him from the water, but when Lamb stood for the first time, excruciating pain shot through his body “like a hot poker in his back,” and he collapsed. The two men stretched him out as comfortably as they could and covered the violently shivering pilot with blankets for the ride to shore.

It was now 0130 in the morning. Lamb had been in the water over four and a half hours!

Once they reached the shoreline, his rescuers sprang into action. One of the men ran to the cabin, grabbed an axe, and chopped a side door off at the hinges to use as a crude stretcher. They laid Allen out on his back and carried him into the cabin, laying him down next to the fireplace, then, ever so gingerly, stripped him of his wet clothes.

A helo from Shaw AFB arrived soon after that and transported the severely injured and distressed pilot to the USAF hospital. So severe was his pain by the time he arrived, it took five aides to hold him down on the x-ray table. Examination revealed he had fractured three vertebrae in his back and two in his neck.

The doctors solemnly explained that in all probability, he would never fly again. “Bull shit!” thought Lamb, and as soon as possible he threw himself into rehab with a vengeance. But, for the first five weeks, he lay immobile. Then, little by little, the actual work of rehabilitating his back and neck began.

Seven months later, he went through a flight status review with the flight surgeons. They explained that if he could do 100 jumping jacks, 100 sit-ups and 100 push-ups in 12 minutes, they would return him to flight status.

“Fine,” replied the determined Lamb, “I will see you in six weeks!” Highly motivated, partly because of the pending loss of flight pay, and an overwhelming desire to beat the odds, he enlisted the help of the wing’s Ground Liaison Officer. The two of them “went at it” two to three hours per day, doing serious rehabilitation work…and it paid off.

Six weeks later, the very fit young Captain Lamb miraculously performed those exercises exactly as required, and in November of 1963, Captain Allen Lamb returned to flying duties. Just eight months after his supersonic ejection and frightening ordeal, in January 1964, he entered and graduated from the Army Jump School.

Thus, one of the most remarkable physical health recoveries in the history of USAF aviation ended. It was a victory over very bad odds by a very determined man.

And, oh yes, Lamb would go on to complete over one hundred parachute jumps with the U.S. Army.

But back then, no one knew what a Wild Weasel was. That adventure for Allen Lamb (and others) was yet to come.

EPILOGUE: While jumping from airplanes gives this writer the willies, it’s been a part of Allen Lamb’s life since his younger days. Before going to Korea as a tail gunner, he bailed out of a burning B-29 during a training mission, one of two crew members to make it out alive. And before leaving for combat in Korea, he switched to B-26s, once more as a gunner. When his plane was hit by AAA over North Korea, he again found himself in a parachute.

With his supersonic ejection from a Hun, he has the perhaps unique distinction of jumping out of a four-engined airplane, a twin-engined airplane, and a single-engined airplane. At the time of this accident, Allen was one of only seven American military pilots to survive a supersonic ejection from a jet fighter. Four of those folks later passed away from injuries received in the ejection. Lastly, at that time, he was the only American military fighter pilot to return to flight status after punching out supersonic and the only one known to have punched out while unstrapped from his seat.

(source: Published in the Intake Magazine, Vol 1, NoXX)