5 February 1958 – On the night of 4–5 February 1958, two Boeing B-47 Stratojet bombers from MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, were flying a simulated bombing mission. The second bomber, B-47B-50-BW serial number 51-2349, was under the command of Major Howard Richardson, USAF, with co-pilot 1st Lieutenant Bob Lagerstrom and radar navigator Captain Leland Woolard. Their call sign was “Ivory Two.”

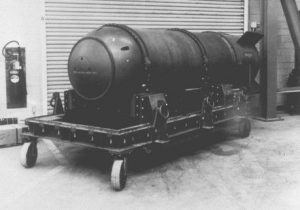

Carried in the bomb bay of Ivory Two was a 7,600-pound (3,448 kilograms) Mark 15 Mod. 0 two-stage radiation-implosion thermonuclear bomb, serial number 47782. The bomb had been developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory. The Mod. 0 had an explosive yield of 1.69 megatons.

After completing their simulated bombing mission, the B-47s were returning to their base in Florida.

On the same night, pilots of the South Carolina Air National Guard were on alert at Charleston Air Force Base with their North American Aviation F-86L Sabre interceptors. The fighters were fully armed with twenty-four 2.75-inch (70 mm) rockets. At 00:09 a.m., the pilots were alerted for a training interception of the southbound B-47s. Within five minutes three F-86Ls were airborne and climbing, with air defense radar sites directing them. In one of the F-86Ls, 52-10108, an upgraded F-86D Sabre, was 1st Lieutenant Clarence A. Stewart, call sign, “Pug Gold Two.”

The flight of interceptors came in behind the bombers at about 35,000 feet (10,668 meters). Tracking their targets with radar, they closed on the lead B-47, Ivory One, from behind. Ivory Two was about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) in the trail of Ivory One, but the airborne radars of the Sabres did not detect it, nor did the ground-based radar controllers.

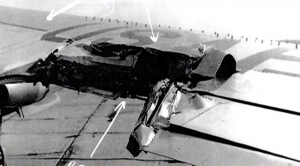

At 00:33:30, 5 February, Lieutenant Stewart’s fighter collided with the right wing of Major Richardson’s bomber. The Sabre lost both wings. Lieutenant Stewart fired his ejection seat. His descent from the stratosphere took twenty-two minutes and his hands were frostbitten from the cold. He spent five weeks in an Air Force hospital. Pug Gold Two crashed in a farm field about 10 miles (16 kilometers) east of Sylvania, Georgia.

The B-47 was heavily damaged. The outboard engine had been dislodged from its mount on the wing and hung at about a 45° angle. The wing’s main spar was broken, the aileron was damaged, and the airplane and its crew were in immediate jeopardy. The damage to the flight controls made it difficult to fly. If the number six engine fell free, the loss of its weight would upset the airplane’s delicate balance and cause it to go out of control, or the damaged wing might itself fail.

Major Richardson didn’t think they could make it back to MacDill, and the nearest suitable airfield, Hunter Air Force Base, Savannah, Georgia, advised that the main runway was under repair. A crash on landing was a likely outcome.

With this in mind, Richardson flew Ivory Two out over Wassaw Sound, and at an altitude of 7,200 feet (2,195 meters), the hydrogen bomb was jettisoned. It landed in about 40 feet (12 meters) of water near Tybee Island. No explosion occurred.

The B-47 safely landed at Hunter AFB but was so badly damaged that it never flew again. Major Richardson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his handling of the incident.

The missing Mark 15 has never been found and is considered to be “irretrievably lost.” It is known as “The Tybee Bomb.”