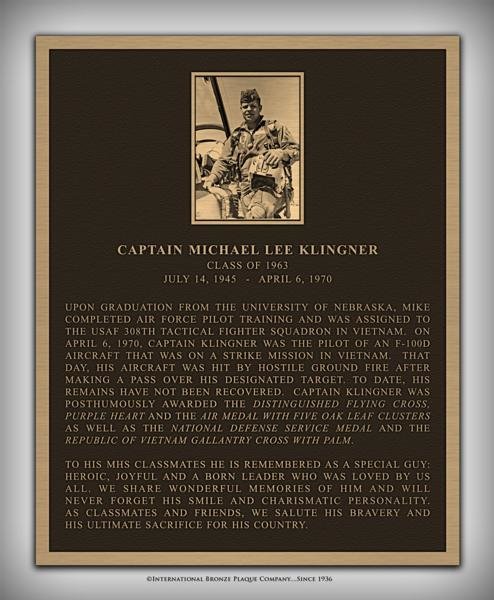

Mike was born in McCook in 1945 and went on to graduate from McCook High School in 1963 and the University of Nebraska at Lincoln in 1967 with a political science degree. While at the University he participated in the AFROTC program and eventually graduated from the USAF pilot training program at Williams AFB in Phoenix, AZ. Jane and Mike were married in August 1968 after having met and falling in love during college.

In December, 1968, as a top graduate of his Air Force pilot training class, he was given first choice for duty and chose the F-100 Super Saber fighter air craft, even though it meant an automatic tour of duty in Vietnam, he left soon after completing F-100 school.

In several of Mike’s letters to his wife from Vietnam before his crash, he made reference to missions over “Litter Land,” an area in which no Americans were fighting and over which very few pilots were flying. In one dated November 1969, Mike described a pass his flight made in which he had one last bomb he had to drop, and he “did it and got the hell out of there.”

After Mike’s plane crash, when Jane was informed of his MIA status, “the details that the officers gave me were incredibly brief for such a life-changing event,” Jane said.

TaskForceOmegaInc.’s report on the crash is as follows:

“On 6 July 1970, Capt. Michael L. “Mike” Klingner was the pilot of the #2 aircraft (serial #56-3278), call sign “Sabre 31” in a flight of two that was conducting an early afternoon strike mission against an NVA supply area located in the rugged jungle covered mountains of eastern Laos. The target was located on a northwest to southeast road that branched off of Rt. 969, a primary artery of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This particular supply route crossed into South Vietnam approximately 25 miles west of the major American base at Kham Duc. The call sign of the flight leader was “Sabre 30.”

When North Vietnam began to increase its military strength in South Vietnam, NVA and Viet Cong troops again intruded on neutral Laos for sanctuary, as the Viet Minh had done during the war with the French some years before. This border road was used by the Communists to transport weapons, supplies and troops from North Vietnam into South Vietnam, and was frequently no more than a path cut through the jungle covered mountains. US forces used all assets available to them to stop this flow of men and supplies from moving south into the war zone.

When Sabre flight arrived in the target area, the lead pilot established radio contact with the Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC). Its crew provided the strike aircraft with current weather and mission data including the fact that the POL dump was located near Binh Tram 44, an established way station and base camp the communists used for a variety of purposes including vehicle maintenance, storage and supply, etc. The ABCCC then handed Sabre Flight over to the onsite Forward Air Controller (FAC) who would direct the attack itself. The FAC marked the flight’s primary target and the Huns successfully destroyed. The FAC then marked the POL dump, which was partially concealed by the jungle canopy, and directed the fighters to make their attack passes from west to east.

At 1346 hours, 1st Lt. Klingner entered his first strafing pass firing his 20mm cannons. Seconds after his rounds struck the cache of 55 gallon drums causing them to explode and burn, his aircraft impacted the forested hillside scattering flaming wreckage for a distance of roughly 100 meters upslope. The target and crash site were located in rugged mountains laced with karsts and infested with a large number of enemy troops roughly ½ mile east of the Song Hounay Pavou River, Dakchung District, Xekong Province, Laos. It was also approximately 3 miles southwest of the Lao/South Vietnamese border, 5 miles due east of BT44 and 28 miles west of Kham Duc. The distance between Binh Tram 44 and Kham Duc was 34 miles.

The pilot of Sabre 30 recounted his wingman’s loss as follows: “I was flying with 1st Lt. Klingner on this mission and believe that he was in the aircraft during the pull up. As he initiated his strafing pass, I observed his 20mm (cannon fire) impact directly on the target. This indicated that up to this point everything was normal and that there was no problem in the recovery from the pass. Approximately 3-5 seconds later, I saw a large ball of fire as the aircraft impacted the groun”

The lead pilot went on, “Since the aircraft cut a long path up the side of the hill in the direction of the recovery, this indicated that 1st Lt. Klingner was attempting a recovery. Had he decided to eject, realizing that he was unable to recover, I feel the aircraft would have impacted closer to the target and covered a much smaller area. This is based on the fact that on a staffing pass all pressures are generally trimmed out.”

Sabre 30 added that just prior to, or as the aircraft was impacting the ground, he “observed an object travel past the fireball,” but he was not able to identify what that object was. When questioned further, he said that it could have been Mike Klingner in the ejection seat, “that the pilot could have tried to eject upon impact, or ejection could have been triggered by the impact.”

The FAC also watched the strafing pass and information gleaned from his debriefing states: “I observed his hits, and he did not appear to make a definite pull-out, but more like a lazy pull with the right wing slightly down. By this I mean that from observing past F-100 strafing runs, I have noted that most pilots after they strafe will make a definite recovery pull-up of this nature. He cut a swath approximately 100 meters up the side of the hill and exploded in a ball of flame. I observed no chute and no beeper.”

A visual and electronic search operation was immediately initiated by the onsite aircrews while the search and rescue (SAR) aircraft that were orbiting in a nearby holding area were called in. As the pilots and aircrews searched the crash site and surrounding area of any sign of the downed pilot, the NVA directed a barrage small arms, automatic weapons and 37mm anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) at the American aircraft. At no time during the search was a parachute sighted nor was an emergency beeper heard. At the time the formal SAR operation was terminated, Mike Klingner was declared Killed in Action/Body Not Recovered.

In May 1992, a US/Vietnamese team under the auspices of the Joint Task Force for Full Accounting (JTFFA) traveled to Hue City, South Vietnam. While the team was examining artifacts on display in the Hue Military Museum, team members discovered two blood chits in good condition, but slightly torn and soiled. One bore the numbers “52971S,†which correlated to the blood chit assigned to and carried on his person by 1st Lt. Klingner.

North Vietnamese Special Reporting that was documented in the logbooks kept by Gen. Vo Bamâ’s 559th Transportation Group, which was based at Tchepone, Laos and controlled the entire Ho Chi Minh Trail, provided additional information about Sabre 31’s loss. These logs are generally referred to as the “559 Document”, and entries correlated to this loss incident yielded the following data: “The 559th Transportation Group reported to Binh Tram (BT) 34 on 6 April 1970 stating that the 28th AAA Battalion of Binh Tram 44 shot down an F-100.” The report added that “the wreckage fell 400 meters from the battle position, and that ‘the pilot paid for his crime.” This report also places the crash site approximately 7 kilometers from BT44 and the battle position of 28th AAA Battalion.

In December 1993, another JTFFA team traveled to Dakchung District, Xekong Province, Laos to investigate Sabre 31’s loss. They interviewed witnesses from the only two villages in the area, but none could provide information about this case. The team also conducted a 200 x 75 meter surface search of the record loss location area, but no material evidence or remains were found.

In May 1995, a third JTFFA team traveled to the area identified in the SAR aircraft logs to investigate this loss and to conduct a site survey. Team members interviewed residents of Ban Dak Vang, the closest village to the SAR log coordinates. The villagers possessed information about 3 aircraft losses, one of which involved a jet. They described it as being large jet, traveling from west to east and that it crashed into an area used by Vietnamese troops as a base camp. The witnesses claimed they had no information about the fate of the pilot, however, they said the Vietnamese thoroughly scavenged the area for metal in 1972. The team was led to a widely dispersed and heavily scavenged F-100 crash site in an intermittent stream bed they believed correlates to 1st Lt. Klingner’s aircraft. The team found and photographed a few pieces of a jet engine. They also walked up the hill and along a ridge overlooking the site, but saw no trace of an impact point. Further, while they found enough wreckage to identify the type of aircraft, they found no remains, life support equipment or personal items.

In February 1997, a fourth team returned to the site visited in May 1995. The team and a witness who had been interviewed earlier went to a new site located 100 meters from the 1995 survey site. They conducted a 400 x 400 meter search and dug a test pit in the stream bed that divided the area. They found multiple bunkers, fighting positions, wreckage consisting mainly of jet engine components, an additional three pieces of metal, two fuel drums and a 37mm shell casing from a standard communist AAA weapon. As with the other surveys of the greater crash site area conducted over the years; no remains, burial site, life support equipment or an ejection seat impact point were found. When quarried about the fate of the pilot and any related material, the witness added that neither he nor anyone he knew had knowledge of personal effects, life support equipment or remains found in or near the crash area.

If Mike Klingner died in the fiery crash of his Hun or ejected too low to the ground to survive, he has a right to have his remains returned to his family, friends and country. Based on the fact that his blood chit was recovered from the Hue Military Museum in good condition indicates that there is an excellent chance the NVA found him, [and] removed him to another location. (1)

Mike’s childhood friend, pledge son and fellow USAF pilot Steve Batty McCook writes on the the Virtual Wall:

“We all still miss you terribly. I put out your flag each morning and give you a salute to say hello and thank you for your gift of love and life. Thank you, old friend and soldier.”

Friend and fellow F-100 pilot, Carrol Johnson wrote:

“35 years ago today, Mike failed to return from an F-100 mission to Laos. I remember the profound shock of everyone in the squadron as if it were yesterday. Mike and I were fellow lieutenants and pilots in the 308th TFS, and flew together and pulled quick-reaction alert duty together numerous times. I always considered him the best wingman I flew with. You could always depend on him, no matter what the mission was.

Mike was fun to know and be around, always in a good mood with a smile on his face. I considered him one of my best friends in my entire Air Force career. Since his death happened so long ago, I will always remember him as “Forever Young”.”

Mayor Flora Lundberg proclaimed July 3, 2000, “Michael Klingner Memorial Day,” at a memorial service to honor his death and service to his country. The official proclamation reads, “due to the delay between his MIA and KIA there was never a memorial service for him” and this has prompted “a public memorial service for Mike during this year’s All-Class reunion.”(2)

Sources: Bio Info/Photos – HonorStates.org; (1) TaskForceOmegaInc.org; (2) TheVirtualWall.org