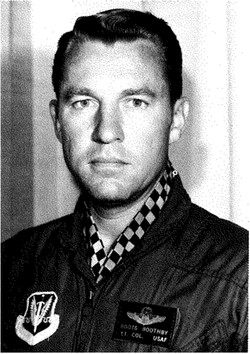

“On 19 September 1967, the 2,000th Phantom II was being flown by Major Lloyd Warren Boothby and 1st Lieutenant George H. McKinney, Jr., of the 435th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Following a Rolling Thunder attack on railroad sidings at Trung Quang, about 10 miles (16.1 kilometers) north of Phúc Yên, 66-7533 was hit in the right wing by a 57 mm anti-aircraft cannon shell. The airplane was badly damaged but “Boots” Boothby fought to keep it under control for as long as possible. Finally, he and McKinney were forced to eject, having come within about 35 miles (56.3 kilometers) of their base.”

“For their airmanship in trying to save their airplane, Major Boothby and Lieutenant McKinney were each awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, which was presented to them by President Lyndon B. Johnson, 23 December 1967, in a pre-dawn ceremony at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base.”

“WASHINGTON (AFPN) — I’d hate to see an epitaph on a fighter pilot’s tombstone that says, “I told you I needed training”. . . How do you train for the most dangerous game in the world by being as safe as possible? When you don’t let a guy train because it’s dangerous, you’re saying, “Go fight those lions with your bare hands in that arena, because we can’t teach you to learn how to use a spear. If we do, you might cut your finger while you’re learning.” And that’s just about the same as murder. —Lt. Col. Lloyd “Boots” Boothby, April 17, 1931, to Nov. 26, 2006

That quote may seem a little extreme, but Colonel Boothby was referring to the Air Force’s urgent need to improve fighter tactics training, balanced against safety, but not at the expense of effectiveness.

Colonel Boothby, who passed away Nov. 26, was an experienced combat pilot and an academic instructor in the 57th Fighter Weapons Wing in the early 1970s. He looked at the Air Force’s declining kill ratio from Korea to Vietnam which was 2.4 to 1 in Vietnam compared to 8 to 1 in the Korean War. He led the effort to fix it. This involved several key steps, starting with a thorough analysis of the engagements over Vietnam.

Colonel Boothby led a series of studies at the Tactical Fighter Weapons Center, which were part of Project Red Baron, examining each of the war’s air-to-air battles. While the subsequent reports noted many accomplishments and even more lessons learned, they highlighted several significant trends. The colonel’s team discovered that pilots of multi-role fighters tended to have such a diverse range of missions that they seldom had a chance to master air combat tactics. They also noted pilots who were shot down rarely saw the enemy aircraft or even knew they were being engaged.

Additionally, few U.S. pilots, before flying into combat, had any experience against the equipment, tactics or capabilities of the enemy’s smaller, highly maneuverable fighters.

In short, the Red Baron Reports called for “realistic training (that) can only be gained through study of, and actual engagements with, possessed enemy aircraft or realistic substitutes.”

Based on this report and Colonel Boothby’s persuasiveness to get himself and Capt. Roger Wells access to an intelligence organization’s restricted collection of Soviet equipment, training manuals and technical data, they developed the dissimilar air combat training, or DACT, program to meet the Tactical Air Command’s initiative of “Readiness through Realism.”

Under the DACT program, Air Force officials had some T-38s painted with Soviet-style paint schemes and flew them based on adopted Soviet tactics.

Because of his combat experience, academic instructor background, and involvement in Project Red Baron and in developing the DACT program, Colonel Boothby served as the first aggressor squadron’s commander when the 64th Fighter Weapons Squadron activated Oct. 15, 1972.

As an instructor, Colonel Boothby proved himself an effective teacher who relished the attention of his captive audience. Ever-animated and quick with a joke or “fighter” story to make a point, he told the pilots he was instructing what they needed to know to succeed. These qualities ensured his students’ attention remained spellbound and eager.

One former student recalled one of the colonel’s more popular attention steps. In typical fighter pilot stance, using his hands to represent a dogfight, he would spray lighter fluid from his mouth across his right hand (palming a lighter at the time) and literally flame the left hand and wristwatch bogie. He generally walked away with a few singed hairs on his hand, but his students received a magnificent visual demonstration of the seriousness of air combat.

Such object lessons ensured this charismatic instructor’s students learned and retained the knowledge they might need to save their lives one day. “(1)

Source: (1) thisdayinaviation.com, © 2017, Bryan R. Swopes

Lloyd W. Boothby, LtCol USAF, Ret., “Headed West” on November 26, 2006.

Lloyd W. Boothby, age 75, retired U.S. Air Force colonel and national sales director, Las Vegas Hilton, died at home Sunday, Nov. 26, 2006, following a courageous battle with cancer.

Lloyd W. Boothby, age 75, retired U.S. Air Force colonel and national sales director, Las Vegas Hilton, died at home Sunday, Nov. 26, 2006, following a courageous battle with cancer.

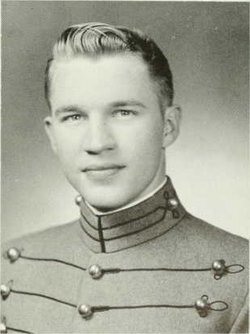

Lloyd was born April 17, 1931, in Washington, D.C. to the late Fred and Bertha Boothby. He graduated from West Point in 1953, and served as a fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force for 20 years. Lloyd served in Vietnam, where he was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses, 12 Air Medals, the Air Force Commendation Medal, a Purple Heart and various campaign ribbons.

Lloyd retired as a lieutenant colonel from the Air Force in 1973, to work for the then – newly built MGM Grand Hotel as vice president, sales and marketing. In 1982, he left to join the Las Vegas Hilton where he worked until his retirement in 2005.

His marriage to Colet Kiefer in 1953, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife, Joyce Boothby; daughters, Diane Boles of Oak Park, Calif., and Colleen Boothby of Takoma Park, Md.; brother, Ronald Boothby of Phoenix; and three grandchildren.

A memorial service [was held on] Friday, Dec. 8, at Nellis Air Force Base. Entombment [was on] Friday, Jan. 12, at Arlington National Cemetery.

In lieu of flowers, please send donations to RRVA (River Rats) National Office, P.O. Box 1553, Front Royal, VA 22630-0033 or to the Nellis Support Group, Nellis Support Team, 911 North Buffalo, #201, Las Vegas, NV 89128.

Published by Las Vegas Review-Journal on Dec. 5, 2006.