In His Words…

My tour as a Misty FAC was the most exhilarating of my 16 thousand hours of service. Something was always happening that provided excitement. Some of those things were scary, some funny, some were “Oh Shit” things, and all of them included gunfire. There was gunfire on almost every mission and most of the individual penetrations into North Vietnam or Laos. As a result, it did not take long to become adept at estimating the bore size of the incoming anti-aircraft artillery (AAA). Our aggressive and continuous “jink” (rapid maneuvering) saved us from a lot of hits and was designed to discourage the gunners from shooting at us in the first place.

One day, I got tapped by a 37mm gunner that wasn’t discouraged. On January 16, 1968, I was flying with Captain Eben Jones. I was in the front seat, and Eben was in the back with all the maps and our 35mm camera. The weather was good, and we had lots of suspicious targets to check out. Our F-100F was just out of IRAN – “Inspect and Replace As Necessary”, and was a beauty – Number 783. It had a new coat of paint, the engine trimmed nicely, and it flew like a brand-new Hun. Our mission had progressed nicely, with a single trip to the tanker, and then “it” happened.

My unit had been given a special assignment. We were to respond quickly to check special targets discovered electronically by EC-121’s(1). The EC-121s listened to radio devices planted along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and reported movement to a secret location in Thailand. These locations were then relayed to us by the AirBorne Command and Control Center (ABCCC). The ABCCC gave us the fix, a Delta point and we rushed in at a gallop. Swish! We went over a bombed-out intersection at 450 knots and didn’t really “see” anything. We decided there might be something we missed and turned around for another pass. Sure enough, there was a cleverly-camouflaged truck or a truck hulk; we couldn’t tell which for sure.

Naturally, we went back again, this time to take a picture with the 35mm Pentax. It was easy, fly over the target, roll up on the side, ease off the G’s, and take the picture. I was too close (or Jonesy couldn’t get the camera far enough out in the slipstream), so we went back for still another pass. This pass was a little better, but by gosh, if we were going to get the goods on the guy, we needed to be a little closer. By this time, we were nearing bingo fuel, but were determined to take one more pass. Since we had to go back over the target on the way to the tanker, we made the pass. Came over the target, rolled up on a wing, and took the photo.

The gunner on the ground must have figured he’d been spotted and fired his 37mm at us. He knew he’d have to “move the gun” that night but it was too tempting for him to keep silent.

Wham! I mean WHAM-M-M!!!, there was a muffled explosion and one utility light came on (very brightly, it seemed). I threw in a jink, while I reached down to the jettison button and cleaned the wing. We S’d out of the area, getting what altitude we could without sucking up too much fuel, and picked up a heading for Ubon.

The flight to Ubon was uneventful. We checked to see if either one of us had any injuries and fortunately we had none. There was damage to the airframe, but Jonesy didn’t fill me in on the extent of the damage to his area and I couldn’t see any in mine. The utility warning light was bright enough to keep me awake and I was on alert for further trouble. The Hun was flying nicely, except for that one warning light. I don’t remember if I said anything to Eben, but at the time I thought, “Boy, are we lucky that we are over Laos, instead of North Vietnam.” I thought we’d have been picked up in no time. (Little did I know about the odds of getting out of Laos).

As we approached Ubon, I made sure the tower knew we had battle damage and were at minimum fuel. I had never actually made a no-flap landing so I was reviewing the speeds and procedures. On the downwind everything looked good and with nothing else going on I said to Eben, “I have half a notion to try the flaps.”

Eben, in an almost disinterested voice, said, “Nah, I wouldn’t bother.” (he could see the gaping hole where the right flap used to be).

The no-flap landing went well, we stopped on the cement, and eased into the de-arming area. When the canopy went up, I saw the damage, and understood why Eben had said not to bother with the flaps.

Though it may not be recorded anywhere, Eben and I brought back the Number 783 with more missing than any other F-100 battle damage RTB. In fact, the external stores and most of the right flap are still in Laos.

(1) EC-121R Batcat – During the Vietnam War some 30 EC-121s were modified from U.S. Navy WV-2 and WV-3 early warning Constellations for and 25 were deployed to Southeast Asia, at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base, as a part of Operation Igloo White. The resulting EC-121R configuration was nicknamed the Batcat. Two Batcats were lost during the war, with the loss of 22 crewmen, one in a takeoff accident during a thunderstorm on 25 April 1969, the other on 6 September 1969, in a landing accident. Four Thai civilians on the ground were also killed in the second crash.Batcat EC-121s were camouflaged in the standard three-color Southeast Asia scheme while the College Eye/Disco early warning aircraft were not. BatCat missions were 18 hours in length, with eight hours on station at one of 11 color-coded orbits used during their five-year history, three of which were over South Vietnam, six over Laos, one over Cambodia, and one over the Gulf of Tonkin. Source:https://myfighterplanes.tumblr.com/post/83625018531/batcat-ec-121r-batcat-during-the-vietnam

The Man…

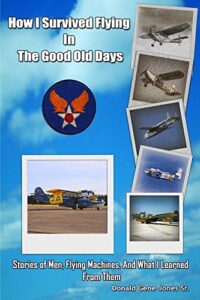

There are few people with an aviation resume that spans decades and generations, from the giant Flying Fortress to the supersonic F-100 but Don Jones is one of them. Spanning a service history from WWII to the Vietnam War, Colonel Jones amassed over 16,300 flying hours in 65 types of military and civilian aircraft during his flying career.

More importantly he’s known as a man who refused to fail on his missions despite adverse weather conditions, low altitude, ground fire and unprecedented aggressiveness from enemy forces. He always responded with courage, aggressive determination, unerring accuracy and calm leadership.

Don’s fortitude is evident in the events leading to his receiving the Silver Star. The commendation was bestowed “for gallantry in connection with military operations against an opposing armed force as an F-100 Forward Air Controller flying over North Vietnam on 27 December 1967. On that date, Colonel Jones conducted attacks over hostile anti-aircraft sites, diving his aircraft through extremely intense barrages of flak, making accurate marking rounds for attacking fighters. After placing the marking rounds, he continued to use his own aircraft as a decoy to draw flak from the less maneuverable, ordnance laden aircraft. By his gallantry and devotion to duty, Colonel jones has reflected great credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.” (source: Veteran Tributes https://www.veterantributes.org/TributeDetail.php?recordID=1421)

1943-1945 U.S. Army Reserve, WWII

1945, 1946-1947 U.S. Army (USAAF), Cold War

1947-1976 U.S. Air Force

1965-1968 Vietnam War