“I was born on 29 June 1942 in Morgantown, WV. I entered the Air Force in June 1960 when I entered the Air Force Academy and was commissioned in June 1964. I married Jerri Klein of Dayton and, after pilot training at Vance AFB, was assigned to an F-4C squadron in England. After upgrading locally I was assigned to the 390th TFS at Da Nang in December 1966.

On 14 June 1967, I went down on a strike mission on the northeast railroad near Kep. Kevin Mcmanus was my backseater. I spent 5 yrs, 8 months, and 4 days in captivity (but who’s counting). During ejection and captivity, I suffered from crushed vertebrae, dislocated shoulders, and broken teeth.

My message: I can forget my years of imprisonment. I can return to a normal life. But what about the young man who lost an arm, a leg, or suffers the effects of a bullet wound in the stomach. He can never forget. Two and a half million Americans served in Vietnam, many of them are now in hospitals or are seriously handicapped. Nor can the mother, wife, or child of an MIA forget. I join you in a prayer of thanksgiving for the return of the POWs and hope for the MIA’s. For a wonderful welcome home and years of support, thank you very much, and may God bless every living one of you.”(1)

Mechenbier was awarded two Silver Stars, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star with Valor Device, two Purple Hearts, the Meritorious Service Medal, 9 Air Medals, and the P.O.W. medal. He separated from the Air Force in June of 1975.

He flew F-100 and A-7’s for the Air National Guard until 1991, and currently a Brigadier General in the Air Force Reserves serving as the Mobilization Assistant to the Commander, Aeronautical Systems Center, Wright-Patterson AFB. He also is a partner in a television production company, and in his free time, he enjoys “golf, golf, golf.” He and his wife Jerri reside in Ohio. They have four children.

Ed Mechenbier entered the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1960 and was commissioned on June 3, 1964. Mechenbier went through pilot training at Vance AFB, Oklahoma, and was awarded his pilot wings in August 1965. He went on to train in the F-4 Phantom II, and after a tour in England, he began flying combat missions out of Da Nang Air Base, South Vietnam in December 1966.

On June 14, 1967, Captain Mechenbier was shot down over North Vietnam while flying his 80th mission to NVN and his 113th overall combat mission. He was immediately captured and taken as a Prisoner of War. After spending 2,076 days in captivity, he was released during Operation Homecoming on February 18, 1973. After his return, Mechenbier flew with the fighter branch of the 4950th Test Wing at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. He resigned his regular commission in June 1975 and joined the Ohio Air National Guard where he flew the F-100 Super Sabre and the A-7 Corsair II for the next 16 years.

General Mechenbier served as the commander of the 162nd Tactical Fighter Squadron with the Ohio ANG from July 1984 to June 1991. In June 1991, he transferred to the Air Force Reserve where he served with the Joint Logistics Systems Center, Headquarters Air Force Material Command, Aeronautical Systems Center, finally as Mobilization Assistant to the commander of Headquarters Air Material Command until his retirement on June 30, 2004. (2)

Ed is “still flying occasionally in a Citation CJ3 with landings being all successful, with no insurance claims”.

(1) Source: https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/m/m109.htm

(2) Source: http://veterantributes.org/TributeDetail.php?recordID=38

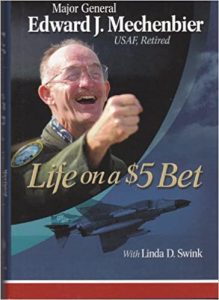

From Gen. Mechenbier’s book “Life on a $5 Bet”

“I had just dropped two tons of bombs on the Vu Chu railroad yard in North Vietnam when Kevin McManus, my backseater, keyed the mike and said, “Looks like we have a half dozen SAMS on our radar.”

We needed to get the hell out of there.

Before rolling in on the target, I had set one engine at idle and kept an eye on the airspeed indicator to know when to light the second afterburner. My plan was to make a sharp turn, head out to sea, and then link up with a KC-135 to refuel before returning to Da Nang.

When the airspeed reached 600 knots, I lit the afterburner, but instead of acceleration, I heard BAM!

That’s when all hell broke loose.

Huge shrapnel-filled puffs of black smoke exploded around my F-4 Phantom as antiaircraft fire pounded the air and 37mm shells streaked past, just missing the canopy. Instinctively, I ducked from side to side. I suddenly found myself in the old “World War II movie, Twelve O’Clock High”, piloting a B-17 and being shot at after bombing cities in Europe.

The red firelight on the control panel began flashing, telling me I had a fire in the right engine. Glancing in the rearview mirror, I saw what no fighter pilot ever wants to see – a raging inferno chasing me. It was my own airplane.

I pushed the red button to extinguish the fire, but nothing happened.

When I flipped the engine’s master switch to shut down the engine, the airplane suddenly made a snap roll to the right, throwing me hard against the inside of the cockpit.

To correct the roll, I swung the stick to the left but it just flopped uselessly back and forth. The ailerons were gone.

With the airplane upside down and losing altitude, I tried the elevators.

Nothing. The hydraulic system was shot.

Not about to give up or let fear take over and drive me to do something stupid that would fry my ass, discovering the rudders still worked, I stomped the left rudder. The airplane stopped rolling and leveled out, but then started to ratchet as it rolled, stopped, and rolled again.

When the airplane spun the second time, I pounded the rudder again. The damaged airplane steadied, but only for a second before it began corkscrewing through the air a third, fourth, and fifth time. I struggled to regain control, but the aircraft continued spiraling and gaining airspeed as it headed for the ground.

Below 6,000 feet, we were in danger of getting hit by small arms fire and with all the aircraft’s systems shot, I was out of options, left with only my skill and training to pull us out of this mess.

At 4,500 feet, the airplane rolled the sixth time. That’s when Kevin called through the headset, “Ed, I don’t think we’re going to make it.”

Still fighting the controls, I wanted to yell at him to shut up and leave me alone. Eve1ything will be okay. I’m a fighter pilot for God’s sake. There ain’t nothing I can’t fix. I’m in control here. I can handle this.

“Ed, I don’t think we’re going to make it.” This time Kevin’s voice was adamant.

Kevin’s urgent nudge brought me to my senses and at 4,000 feet I gave the order, “Bailout, Kevin! Bailout!”

Kevin didn’t wait for the second bailout order. “Sayonara, Ed,” he said, and pulled his ejection seat handle at the same time I pulled mine. Our seats shot out of the airplane simultaneously, but upside down. Not a textbook ejection.

A blast of air hit me as I rocketed from the airplane. Leaving an F-4 with a Roman candle attached to my rear end was like being shot out of a cannon with twenty-one men sitting on my chest. The pressure of the g-force squeezed so hard I thought my lungs would collapse.

It took only one and three-quarter seconds from the time I ejected until my parachute snapped open. And before I had a full chute, my airplane hit the ground, exploding into an orange ball of flame. Without Kevin’s warning, I would have ridden the airplane into the ground without ever giving a second thought to bailing out.

Hanging in my parachute harness, I looked up and saw holes in the canopy.

Looking down I found out why. Angry peasants were taking potshots at me. I was a clay pigeon on a skeet shooting range floating right into their midst. All I could do was pray please don’t shoot me.

My heart pounded as I drifted toward a small fanning village surrounded by a patchwork of rice paddies. In any other situation, the scene below would have been a photographer’s delight, a pastoral postcard, but with bullets sailing past my head, the picture was anything but serene.

I disconnected my facemask, pulled my radios from my survival vest, and then smashed them together, breaking the batteries and antenna so the Vietnamese couldn’t use them to lure rescue helicopters into a trap. I detached the survival kit from behind my legs and watched my food, water, raft, poncho, and signaling mirror, all the equipment needed for survival, fall below me.

Having a .38 caliber pistol as my only protection, and not wanting those peasants to think I was going to shoot it out with them when I hit the ground, I threw the pistol away. It probably landed in a rice paddy somewhere and may still be there for all I know.

With my parachute full of holes and no way to maneuver it, I was at the mercy of the wind. As my luck would have it, I landed on the pitched roof of the only building within sight. I rolled off, falling twelve feet and tangling myself in the shroud lines on the way down. I lay on the ground like a Christmas package wrapped in a silk cocoon. So much for all my training hanging for hours in a harness practicing the correct parachute landing-eyes on the horizon, feet together, and knees slightly bent. Nice in theory; not practical in reality.

I saw Kevin make a perfect two-point landing in an open field not far away, but before he had gathered his chute, and before I could free myself from my tangled web, we were surrounded by a group of non-uniformed militia carrying every conceivable type of weapon from high-powered automatic rifles to guns so old they could have been turn-of-the-century flintlocks, and they were all pointed at us.

From the menacing expressions of these rebels, it was apparent they weren’t going to invite us to dinner. Article II of the Code of Conduct says: I will never surrender of my own free will, but with a hundred guns aimed at me, it was hard to muster my free will.

Two men wearing belted pants and buttoned khaki shirts yanked off my helmet and parachute harness, and then, with what seemed like thirty-foot long machetes, started cutting through the shroud lines. Once I was untangled, one man pulled me to my feet and began slashing through my G-suit. He then ripped off my flight suit as another man stripped me of every stitch of clothing except my tee-shirt and shorts. They didn’t stop there; they took my dog tags, Geneva card, boots, socks, gloves, and wristwatch.

Hundreds of peasants emerged from the rice fields and surrounded us to watch the proceedings. Several barefoot children, too young to appreciate the political aspects of war, threw rocks at us, while others gathered around, staring at the two strange men who had fallen from the sky. A group of middle-aged citizens wearing black pajama-like clothes and conical hats yelled at us, and although I didn’t understand what they were saying, their angry shouts and fist-waving suggested they were a bit unhappy that we had just dropped in. Interestingly, however, a circle of older people stood off to one side, arms folded, with no expression of animosity as if to say, “Sorry about your luck, fellows.””

To read a portion of the book and order it for your library go to https://www.amazon.com/Life-Bet-General-Edward-Mechenbier-ebook/dp/B00SX9TQPA