SIDEWINDER-13

In early 1966 I was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division, Phouc Vinh South Vietnam, as a FAC. Flying the 0-1 Bird Dog and directing airstrikes proved to be more fun and challenging than I had anticipated. I flew almost daily. The average mission was about four hours and after six months I had amassed over 600 hours in the little bird. Upon returning from a late afternoon mission, I stopped by the division headquarters bar for a cold, tall Crown Royal and soda.

As I sipped my second swallow, a frantic young army enlisted man burst into the bar and ran to my table. “Captain Harrison, Captain Harrison, you’ve got to help! We had a helicopter with five people crash just short of the base. Please help us find them” he said excitedly. I poised for a moment. We were not allowed to fly at night or in weather. Many of the instrument “night lights” were inoperative and not maintained. Furthermore, the attitude indicator precessed excessively and we had no landing lights.

I would not be able to advise anyone about my decision! I paused for a moment but decided to give it a shot. It just might save five of my brothers in uniform from almost certain death! I jumped in my jeep and hurried down to the flight line. It was almost dark. Luckily, the maintenance crew was just buttoning up my bird. No rockets but a full load of fuel. One had a flashlight in hand which I grabbed and jumped in the bird, fired up, and took off! About five minutes east of the base I came upon a circling helicopter and a Gooney Bird dropping flares.

I immediately asked who is in charge? No one responded, so I said, “This is Sidewinder 13, I am in charge!”

Since there were no objections I preceded to give orders. I told the flare ship to stop dropping the flares. The terrain was a heavily forested tree cover below us, and no one could readily see a flashlight. The flares and resulting smoke haze only exasperated the problem. I then asked the Chopper pilot where the missing aircraft was coming from. He gave me the name of a location I had never heard of so I asked if he knew the reciprocal heading. He said 040 so I instructed him to accompany me as we weaved back and forth over the most likely course that we thought the chopper had taken. I instructed the C-47 to fly in a zigzag course further south.

After about an hour and a half, I miraculously spotted a faint glimmer of light! It was about four or five miles north of where we had originally been searching and was only visible for a split second at a certain angle. The chopper pilot confirmed. I directed the Gooney Bird to drop a flare over this area so we could see the treetop configuration. We needed a distinctive landmark. There was nothing that really stood out in the area but a rather unusual treetop formation was helpful. Everyone agreed we could possibly find it again. If the flashlight burned out we would only have that image to orbit. I asked the C-47 if they had any packages of dye they could use to mark the tree canopies but they said no.

I then instructed the Gooney Bird to take a Tacan bearing and distance from Bien Hoa. Next, I called Bien Hoa rescue and requested a chopper be deployed, explaining we had a flashlight apparently from a survivor in a downed helicopter with five persons on board. I then gave him the approximate location. His was response was, “Are there any friendly’s on the ground?” I said, “yes we have five.” He asked, “Is the area secured?” I said, “I am circling at 100 feet above the trees and no one is shooting at me.” He repeated, “Do we have friendly’s securing the area on the ground? I said, “I am not asking you to land. I want you to lower a jungle penetrator with a flashlight and a radio attached down through the trees, and see if they speak English!” His response was, “ We cannot come if the area is not secured!” I sarcastically asked, “Do you know we are at war?” He repeated that he could not dispatch a rescue helicopter if the area was not secured. I spoke with the Army chopper and asked him to request a Chinook from the closest base.

I knew this would take some time and I was worried about the flashlight going out. Since I had no communication with the man holding the flashlight I could not tell him to save the battery until a rescue helicopter arrived. About 30 minutes later I was advised a chopper was en route but would not be there for 30 more minutes.

At my last fuel check, I had near half a tank remaining but now as I glanced down at my fuel…I had ⅛ of a tank. I was so engrossed with this tense operation I broke the cardinal rule “always check your fuel!” I had never flown with less than ⅛ of a tank and was not confident the fuel gauge was that accurate. I informed the participants that I was low on fuel and reluctantly had to I saw nothing but total blackness! I called the Army for a flare. I knew they were reluctant but I could not even contact them on the radio.

A cloud deck had come in at just 600 feet over the area. I can tell you this is an eerie feeling, tooling just under a 600 ft deck and not being able to see anything! I knew I had to try and make Bien Hoa. I turned to what I thought was a heading to Bien Hoa and climbed to 800 feet. The weather to the south was clear. I called Bien Hoa for a DF steer. They responded, ”DF inoperative”. I was pissed, so I called Saigon Tower for a DF steer. Their response: “Sorry Sidewinder, our DF equipment is inoperative.”

My fuel was now showing barely above empty and I could not see any lights. I maintained 800 feet altitude and headed for what I thought was Bien Hoa. Luckily at this point, I picked up the split beacon for the Bien Hoa tower on the nose. I called the tower declaring Emergency Fuel and my approximate position. As I neared the base they cleared me to land. At that same moment, the engine sputtered and quit! Damn, it was silent, only the wind at the side windows. I barely made the runway, landing at a 45-degree angle to the runway and rolled to a stop barely off the inside edge of the runway.

The tower instructed me to clear the runway for an F-100 scramble! I saw the two birds running for takeoff. Not knowing what else to do I quickly jumped out of the bird and ran to the rear and put my shoulder to the rudder and pushed the 0-1 off the runway as two F-100s came roaring by! It was frightening! I had never been that close to an F-100 in burner! I sat on the ground and caught my breath. Shortly thereafter a jeep came to pick me up and took me to base ops.

After a cold glass of water, I walked over to the Rescue Flight Operations Center. I was not in a good mood. I was met by a Major, the duty officer. I told him what had transpired and I could not believe that my request for rescue had been denied. He informed me that on the previous day they had lost a chopper and a crew during an attempted rescue, hence he was reluctant to dispatch his remaining assets for a night rescue that was not secured.

Though I saw his point and was somewhat appeased, I asked how he could justify refusing to fly a rescue mission as the war had not ceased. I noted that as a fighter pilot tasked to support ground forces, we never hesitated to respond and did our utmost to save those in need, even if we had lost a pilot the day before and the risks were high! Furthermore, I only asked that the crew hover and lower a penetrator with a flashlight and radio attached. If we could confirm friendly we could a rescue operation at daylight. I felt he should have launched and evaluated the situation upon arrival rather than deny my request. He did not respond. I walked over to a squadron sleeping quarter where I frequently found an empty bunk, removed my boots, and collapsed in an unoccupied bunk. Not a good day at Black Rock.

I awoke the next morning as bunkmates were rising for the day’s work. I borrowed a razor, shaved, and showered before calling my boss to tell him what had happened and where I was. He simply said, “Good, I want you to pick up a new bird and proceed to the army airfield near Nui Baden (I do not recall the name of the post ). They had a concrete runway and we could put in airstrikes in support of the Special Forces Camp on the Cambodian border. Jim told me to hustle; the FAC “ on station needed relief.” I quickly stopped by the PX bought a toothbrush, toothpaste, and two pair of shorts, and caught a ride to Base Ops.

As I took off I wondered if the downed chopper crew had been rescued. It has bothered me to this day. I feel someone would have thanked me if they were rescued…but that never happened. I assumed they were not. The army gave me an Army Commendation Medal for my six months service. A few days later I was transferred to the 90th TFS for checkout in the F-100. After a few missions, I was then transferred to the 531st as a flight commander for the remainder of my tour.

I enjoyed flying the Hun in combat and had a few rewarding and challenging missions at Bien Hoa, but none compared to numerous hair-raising stories that I had flown at Phouc Vinh, down among the spinach! I was very thankful that I had the opportunity to serve as a FAC with the Big Red One as well as fly the Hun in combat! The missions are still vivid in my mind and I recall the cool wind blowing in my face throughout the open windows of my little airplane! – Sidewinder13.

Story 2

“In a deployment from Myrtle Beach intended destination Adana Turkey my leader aborted , nose wheel pin not removed. After multiple attempts he directed me to join the flight. It was pitch dark and i never crossed the ocean. I flew at 400 knots for over 30 minutes before finding my squadron mates.

All went well through two air refuelings, but as I climbed out over Spain my cockpit temp went full hot. I was instructed to go 100% oxygen and open the outside air duct. Suddenly hot cockpit was no longer a problem! I had cracked the right rear canopy in refueling, It blew out.

I could not hear any radio transmissions and was COLD. I pulled up on lead’s left wing and pointed at the missing portion of the canopy. He ackowledged and lead me into Chaterous AFB France in heavy rain at 300 ft and one mile vis. He visually told me to land and then he went around ,,,,so much water on the runway he feared a formation landing. I spent 6 days at Chaterous with no civilian clothes and little money I could borrow from fellow pilots When a replacement canopy finally arrived I flew my first mission in USAFE solo to Wheelus!

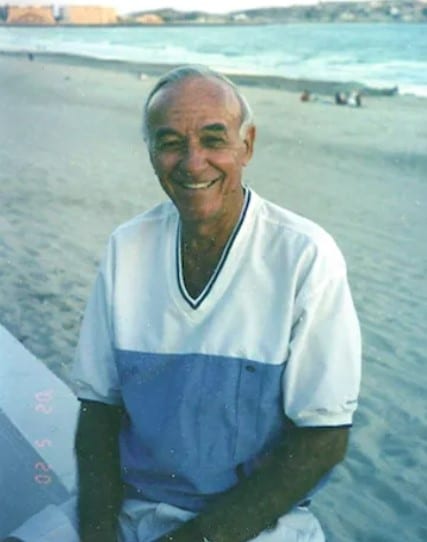

After leaving the USAF, Walt says he “retired and traveled. I’m a lucky old SOB.”

John “Walt” Harrison, Col USAF, Ret., “Headed West” on October 23, 2023.

Colonel John W. Harrison slipped the surly bonds of earth on October 23, 2023, at his home with his family. Colonel Harrison was born in Sumter, SC to Evadne and Nick Harrison on April 27, 1933. He graduated from Edmund High School in 1951 and attended Clemson A & M University, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Architecture in 1955. One year before graduating from Clemson Walt married his long time sweetheart, Ann Lowder from Oswego, SC. The couple welcomed one son, Bruce & one daughter, Lisa.

Colonel John W. Harrison slipped the surly bonds of earth on October 23, 2023, at his home with his family. Colonel Harrison was born in Sumter, SC to Evadne and Nick Harrison on April 27, 1933. He graduated from Edmund High School in 1951 and attended Clemson A & M University, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Architecture in 1955. One year before graduating from Clemson Walt married his long time sweetheart, Ann Lowder from Oswego, SC. The couple welcomed one son, Bruce & one daughter, Lisa.

Upon graduation, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the United States Air Force to serve a two-year ROTC commitment, but his immediate love and passion of flying altered his plans and he elected to serve a military career. Walt flew fighter aircraft over a 30-year career, including T-33, F-84, F-100, F-104 & 0-1 with over 4500 hours including 735 combat hours in Vietnam.

His military decorations and awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters; the Meritorious Service Medal with one leaf cluster; the Air Medal with twenty oak leaf clusters; the Army Commendation Medal; the Presidential Unit Citation; the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with V Device and three leaf clusters; Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal; National Defense Service Medal; Vietnam Service Medal with two bronze Service Stars; Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal and Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross.

Walt had the personality and natural charisma to make friends anywhere he went and under any circumstance. He was a man who had many lifetime stories which he loved to share with his friends and family. He was a truly great man whose impact will be forever felt by his family, who loved him dearly. His ability to sacrifice, provide support and advice, forgive and love will be forever be engrained in all he knew.

Walt is survived by his wife Ann Harrison of 69 years, son Bruce Harrison, daughter Lisa Softley and grandsons Ken Enhelder and Ryan Softley , five great grandkids ; Gage, Zack, Addison, Rush & Lucy.

Services with full Military Honors [were planned] at the Veteran’s Memorial Cemetery at 23029 N. Cave Creek Rd at 12:30 pm on November 20, 2023. Reception to follow.