I was not an aviation enthusiast as a kid. I went to college and got my engineering degree and while enrolled in ROTC got my commission.I just decided I wanted to fly. I was lucky really enough to finish pilot training and get selected for fighters. I liked it. I was 21 when I went into the Air Force and 29 when I did my first of two tours in Vietnam as a Captain.

I just decided I wanted to fly. I was lucky really enough to finish pilot training and get selected for fighters. I liked it. I was 21 when I went into the Air Force and 29 when I did my first of two tours in Vietnam as a Captain.

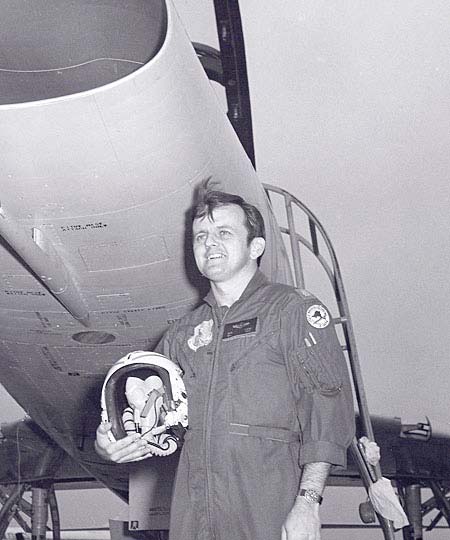

The first fighter I flew after pilot training was the F-100 Super Sabre. The F-100 was the main fighter bomber that the U.S. Air Force flew in South Vietnam. When I went to Da Nang in South Vietnam I was flying F-104 fighter jets.

The F-104 Starfighter is a very fast airplane; faster than the F-4 and a little bit faster than the F-105. We were able to keep up with the (F) 105 in North Vietnam where the F-4 couldn’t have. … Our F-104 mission was patrolling over the Gulf of Tonkin in the early days of the Vietnam War.

In 1966 on my second tour, I was stationed at Udorn Air Base in Thailand and flew F-104s into North Vietnam. Those who flew over South Vietnam had a yearlong tour of duty. Those flying missions over North Vietnam were committed to 100 missions, usually fulfilled in seven months.

My 100-plus missions over North Vietnam were a mixed bag of very dangerous to some ‘milk runs’ — easy missions with little threat from enemy anti-aircraft fire or SAM missiles. The toughest ones were when I was escorting Wild Weasel F-105’s that were trying to suppress — and kill — surface-to-air missile sites that were a major threat to the strike force of fighter bombers.

I recall one mission I was on Aug. 1, 1966, when we were flying just northwest of Hanoi — on the infamous Thud Ridge, named after the many F-105s that try to use the ridge to shield us from the enemy radar in the area. My operations officer was flying in the flight in front of me and was shot down by a SAM missile; a young captain — who I had dinner with the night before the mission — was shot down in the flight behind me.

Neither one of them survived. I luckily made it safely for the 22 minutes of “busy work” as we suppressed the missile sites that were trying to shoot down the F-105 fighter bombers that were hitting the Thai Nguyen steel mills just a little north of Thud Ridge. Needless to say, it was a little disconcerting to have two of my squadron mates shot down that day. We also lost an F-105 and a reconnaissance F-101 on that mission.

Flying missions over North Vietnam, we pilots knew our survival rate was 50-50. We had about 15 F-104s in my squadron and about 18 pilots. In the first three months, we lost five airplanes. Of these five aircraft, we only rescued one pilot. Three were killed in the shoot-downs and the fourth, my flight commander, was captured by the North Vietnamese and was tortured to death in the notorious Hanoi Hilton prison.

The odds of survival got better later on in my tour and I completed my 100 missions in December 1966. Preparation for these missions was just like we were trained for: Know your aircraft, know the enemy threats that you will face, pray a lot and do your best to believe that you will be able to survive.”

I completed my Air Force flying tour as a squadron commander on A-10 Warthogs when they first came out. The Warthogs are still being flown in Afghanistan.

After my tours of duty, I went to Washington, D.C., and worked for President Ronald Reagan at the White House which was a great honor. I was on the National Security Council staff and as director of political-military affairs.

I think it’s hard to tell the story of Vietnam unless you tell it from an air perspective. Coming back from Vietnam, many servicemen faced an ungrateful nation of protesters who would spit on them and call them names. I was on a military base and did not have to endure what some of our returning veterans did when they went back to civilian life.

I tell people that we who fought and flew in Vietnam did it because that was what we were trained to do. We were volunteers — career officer in my case — and we just did our job to the best of our ability. The air war was tough because of the micromanagement from Washington who did not allow our military leaders to prosecute the war in the best way from a tactical and strategic perspective.

For example, when I was there in 1966, we could not attack enemy MiG aircraft on the ground at the bases around Hanoi — not very smart, but some in Washington were afraid to diplomatically upset the Russian or Chinese advisers that were assisting the North Vietnamese on those bases. However, we followed the rules and did our job every single day, on every single mission.

Source: Edited from an interview with Sherry Barkas of the Desert Sun, July 12, 2014.