This story by Ron Deyhle originally appeared in Issue 42 of The Intake.

We Lost Our Blue-Eyed Boy – by Ron Deyhle

The chronicles about our KIA or POW brethren are plentiful (and painful) to all the folks left behind who knew them, where ere they may have been on the globe when they got the sad news of these permanent losses. Equally plentiful and painful (maybe even more so) are the losses that fall in the middle-ground category of MIA. Why? Most likely because of the nagging uncertainty particularly visited on those who “were there, close up and personal” in terms of physical proximity to the last known location of the buddies who didn’t make it home “that day.” SSSer Ron Deyhle has captured that continuing pain about the loss of a close buddy who remains in that dreaded and painful category of Missing in Action … a buddy named Clive Garth Jeffs.- Ed.

Biography, Etc.

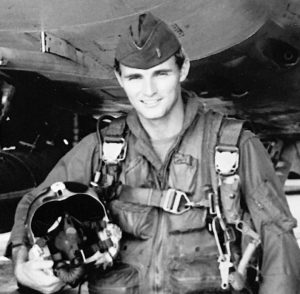

He was the best ping pong player I have ever seen, even better than Forrest Gump. He was also a great stick and well-liked squadron mate of the 614th TFS at Phan Rang (PRG). On March 12, 1971, he was suddenly lost to us. He probably met the pale horse and rider that day, but his story is still shrouded in mystery. [Pale Horse and His Rider is a popular Blue Grass song recorded in 1951 by Hank Williams, Sr.]

When a pilot is lost, it is human nature to focus mainly on the event. But these dedicated American warriors, who gave the ultimate sacrifice, had much more. They had a family, a past, a future … all lost. And they had people they loved, and who loved them. Clive Jeffs, at 28, had lived a full life. Clive was born October 12, 1943, in Provo, Utah. He was a confirmed member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) who was also a deacon, a teacher, a priest and an elder in the church.

Clive graduated from Carbon High School, Price, Utah, in 1961. He then attended the College of Eastern Utah, during which Clive was called to serve a mission for the LDS church in the eastern Atlantic states. He was released from his mission in December 1964, whereupon he returned to college and graduated in 1968 from Utah State University with a double major in psychology and business administration.

He loved cars, music, swimming, water skiing, tennis, sports and, yes, ping pong. He was an all-American boy and carried a strong allegiance to his country and to his church. So, Clive entered Officer Training School at Lackland AFB. He graduated in September 1968, with honors and was assigned to Randolph AFB for pilot training. There he was number 2 in his class, received the “Most Valuable Student” award, and therefore had his choice of assignments, choosing F-100 fighters at Luke AFB.

In July 1970, after advanced gunnery school at Luke, he was assigned to the 31st TAC Fighter Wing at Tuy Hoa AB, Vietnam. When Tuy Hoa AB closed in September 1970, all pilots with 181 or more days in country went home. As relatively newbies, Clive, Fred Tomlins, and I were transferred to the 35th TFW, 614th TFS at Phan Rang. It was there that I came to know Clive well, as a solid, reliable pilot and close friend. As with all lieutenants, he and I spent a good amount of time on the night alert pad. He had over 200 missions when that fateful day [March 12, 1971] arrived.

Clive was Lead, Devil 61, and Fred Tomlins was Devil 62. The mission was a good one, in the tri-border area with recovery at Phu Cat and then back to the tri-border region in a turnaround mission. F-100D #415 was one of the two birds assigned for this flight by Maintenance and it happened to be Fred Tomlin’s airplane. So, Fred naturally asked Clive if he could fly “his airplane.”

But #415 was armed that day with napalm and Clive wanted to fly it. He told Fred they could switch birds at Phu Cat for the turnaround-homeward bound mission. So Clive and fate took aircraft #415. Fate was (indeed) the hunter that day (as put in the 1961 memoir by aviation writer Ernest K. Gann). Clive led off. Tomlins joined on his right wing and tucked in tight because of clouds. They broke out of the clouds at 8-10,000 feet, and Fred unhooked his zero delay lanyard. Clive never gave the signal for that 10,000-foot check. Not long after, they were 10-11,000 feet. Clive came on the radio and said, “I have a fire light and am flamed out.” These were the last words ever heard from Clive Jeffs.

Tomlins told him to “try a restart and if it doesn’t work, get out before you get in the clouds.” There was very high terrain below the cloud bank and Fred wanted to keep Clive in sight. Clive was in a slight descent while most likely trying a relight, which failed. The next thing Fred saw was the canopy blow and Clive was up the rails and gone. Fred was heavy and fought off the stall as he made a hard left turn to keep Clive in sight. They were on the 300-degree radial at 47 miles DME from PRG. Fred got around his hard turn and very briefly saw the chute’s orange and white panels rapidly descending into the clouds. (On later reflection, Fred could not confirm that he saw Clive in the chute.) Fred made the Mayday call and a chopper was launched from Da Lat.

There was never an emergency beeper or radio call from Clive, nor any response to Tomlin’s radio calls. Fred pickled off his MK-82s and stayed in the area until he was low on fuel, then headed back to PRG. Blade 1 & 2 were scrambled and passed Fred as he headed back to PRG. Scott Madsen and I were headed to Cambodia for a mission, and when we heard the Mayday call, we came back to the bail out area until we were minimum fuel, and then we RTBed.

After Fred landed at PRG, he was debriefed at the Command Post and then jumped into an O-2 flown by one of our “Walt” FACs. They searched for two hours in the area where Clive punched out. They saw many buildings with bad guys (Vietcong), but the general terrain was rough, high karst cliffs and heavy jungle. The next day Fred went out again in an O-2 and searched for 8 hours. Searches continued by SAR forces for 10 days. No sign of Clive Jeffs. No beeper, no radio, no chute, nothing. He had been swallowed up by Vietnam!

Epilogue

Our Ops Officer, Major Joe Banks, asked me to send his belongings home, which I did with heavy heart. Clive’s father was Clive Livingston Jeffs. His mother was Katie Bell Sitterud. They were divorced when Clive was a boy. Clive was close to his father and had a good relationship with his stepfather. Clive’s mother died before he went to Vietnam. His sister, Karolyn Hall, was a very close sibling, and I am still in regular contact with her. I communicated with both families and had many heartfelt, emotional letters from them.

It has now been 49 years since we lost blue-eyed Clive Jeffs on 12 March 1971 and still no answers, only confusion, and frustration. There have been 11 investigations by the Joint Casualty Resolution Center (JCRC) and they have scoured the area with search crews. They had found 3 wrecked F-100s, but not Clive’s, until recently. They found AC #415, but no human remains or additional clues to his fate. The JCRC has contacted me, Lee Howard, and Fred Tomlins multiple times to see if our memory could turn up new clues. In 1974, JCRC investigators visited Kron Bong District, and one villager stated he saw a chute in the trees at the time of Clive’s disappearance, but no body or grave was found. JCRC has Karolyn’s DNA on record in the event of recovered remains. What happened to Clive Jeffs?

Here’s some conjecture.

Perhaps Clive’s airplane took a small arms fire hit on climb out. Phan Rang was surrounded by mountains and we occasionally saw small arms fire on climb out to the north over the mountains. But there is no evidence, so it was probably engine failure, an operational loss.

The canopy was blown off, so he did not eject through the canopy. The seat and Clive were ejected, but Fred was not sure he saw Clive in the chute, only that he saw the orange and white panels. The chute should have 4 panels; orange, white, brown and green. Fred thought the chute may have been a collapsed streamer and that is why the chute descended into the clouds so quickly and why Fred could only see two color panels.

An old head at Tuy Hoa told Clive and me not to place the emergency beeper on auto mode because if you were unconscious or severely injured the blaring of the beeper would clutter guard and make communication in rescue more difficult. Clive and I talked about this and I think he may have followed this advice. This is not such a breach of aviation as it seems, as documented in Search and Rescue  Operation Combat Experiences, Lessons Learned #72, Section II, Page 7, Paragraph 5. “Since the personal locator beacon (beeper) signal interferes with other survival radios and airborne communication, maximum effort should be made to turn the beeper ‘off’ before attempting voice contact with rescue forces. Before abandoning the parachute, the parachute beeper must be turned ‘off’ to prevent it from blocking voice contact.”

Operation Combat Experiences, Lessons Learned #72, Section II, Page 7, Paragraph 5. “Since the personal locator beacon (beeper) signal interferes with other survival radios and airborne communication, maximum effort should be made to turn the beeper ‘off’ before attempting voice contact with rescue forces. Before abandoning the parachute, the parachute beeper must be turned ‘off’ to prevent it from blocking voice contact.”

Another document helps us even more in understanding Clive’s possible thought process. House Committee Print No. 16, American Missing in Southeast Asia Committee on Veterans Affairs: “Early during hostilities emergency radios were customarily rigged to activate automatically upon ejection. Later, at squadron commanders’ discretion, most pilots elected to switch to manual activation of emergency radio sets. Emergency beacons were part of the ejection systems. Pilots could eject using either manual or automatic activation of the beacon. The signal was similar to that of the emergency radio beeper. Later, in the 1960s, beepers were modified so they could be automatically or manually activated.” When at PRG we carried two radios in our survival vest, and an emergency beacon (beeper) in our ejection equipment.

I think Clive followed the experienced Tuy Hoa pilot’s direction. I believe his automatic emergency beeper was turned off, in manual mode. If he did not do this and his beeper was in automotive mode, then I believe he did not get a good chute, so no beeper activation.

He may have had seat involvement if his zero delay lanyard was still connected. The butt kicker may have malfunctioned. He could have been killed in a jungle or karst parachute landing.

He may have survived, but been immediately captured. This was a heavily VC infested area of Vietnam. Before Nixon’s Cambodia invasion, Phan Rang was the most rocketed base in Vietnam!

Unconfirmed Reports

Clive’s name came up on Radio Hanoi shortly after the loss (they commonly claimed capture without proof). The most amazing story was that a chopper crew picked up a bearded, light-haired Caucasian who had escaped from a POW camp and killed a guard. One report says he was taken to Saigon, another to PRG hospital. Everything was being kept secret because of the possibility of a rescue of other POWs. I talked to Scott Madsen, who was in the command post, and he remembers the story second-hand. Many other pilots heard and relayed this story, but after 48 years, the fog of war and time have diminished memory and no one can provide a first-hand account. There are no records or information in DOD files to confirm this event.

June 21, 1978, DOD declared all POW/MIAs but one, RF-101C pilot Charles Shelton, as KIA. This closed the ugly door and allowed finalizing payment and service benefits to families. Death Certificates were generated for all except Charles Shelton, who was issued a death certificate in 1994 at the request of his children.

Closure

Clive Garth Jeffs’ memorial stone is at the Huntington City Cemetery, Emery County, Utah. Vital Dates are October 21, 1943 — March 12, 1971. He missed out on so much life, but his sister Karolyn said he was a man of faith and that she knows she will see him again soon. As Admiral Torrant said in The Bridges at Toko-Ri, (Michener, 106), “Why is America lucky enough to have such men? They leave … and fly against the enemy … where do we get such men?”