Some people don’t fully appreciate Fighter Pilots!

(615th TFS June 1968) I was in a flight of 2 F-100 lead by the Vice Wing Commander on a close air support mission 100 miles south of Saigon just pulling off our first pass when I looked down and confirmed that I was losing power although I didn’t feel or hear any hits on the airplane. Luckily, I was turned toward Bin Thuy AB about 15 miles away. I couldn’t see the small base because it was obscured by cumulus clouds. The runway was tricky, it was only 6000 feet long without a barrier at the end. On the descent, I broke out of the clouds over a wide river, jettisoned all my remaining bombs and fuel tanks, and was in a good position to make the runway.

I had lots of airspeed and concentrated on touching down at the very lip. Luckily the drag chute worked and I managed to stop the airplane just before the over-run. That’s where the fun started. This was at about the midpoint in a year’s combat tour and I was getting comfortable flying and feeling good about getting this broken jet down safely. Some might even say I was a bit cavalier.

Here’s the humorous part… A Jeep pulled up and but the driver didn’t look too happy. He was an Air Force Major and informed me that this was not a fighter base. After seeing all the armament wires and jettisoned drop tank fuel dripping my airplane, he wanted to know what I did with my bombs. I explained that they were in the river along with my fuel tanks but reassured him that the weapons were not armed. I wondered what has caused my power problem and saw that the aft turbine section looked like a weed whacker had attacked it, some of the turbine blades jagged or missing. This didn’t seem to impress the major and he told me that I was in big trouble since I released my ordnance “outside of his designated ordnance disposal area”. What a guy!

About that time, I decided to leave him as soon as possible since he didn’t appear to appreciate the skilled flying and fighting part of the Air Force. The AF Major drove me to his base operations office and told me to write up the incident while he reported it to his boss. At the same time, I noticed a C-123 starting his first engine and saw a way out of my “catch 22” situation. I grabbed my helmet and headed for the airplane waving my arms until the Pilot signaled me to come aboard. I hopped in his jump seat and discovered he was going non-stop to my home base and was happy to be able to take me back. There’s another side to the story, but I don’t think the Major at Base Ops follows the F-100 website.

The serious side of being a Fighter Pilot.

I wanted to be in the Air Force. The recruiter told me that the last Aviation Cadet Pilot slot was filled, but I could be trained as a Navigator or Electronics Warfare Officer and go to Pilot training in “a few years”. It turned out to be five years when I was accepted for Pilot Training.

This stroke of fortune led to flying the F-100 during TET Offensive in Vietnam and later in Spain in new F-4 E’s and A-7 D’s. I flew 292 combat missions in 1968. During the Tet Offensive February 11–17, 1968, five hundred forty-three (543) Americans were killed in action, and two thousand, five hundred and forty-seven (2,547) were wounded. That year the total US losses were sixteen thousand, nine hundred (16,900), the worst yearly toll of the war. Almost all of our TET missions were Troops in Contact and I had less than 200 F-100 hours. I’ve reconstructed one mission with an accurate 50 caliber automatic that hit both of us! In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union had tried to match the US capacity for weapons…an impossible task, so in October 1962, as a 1st Lt, I found myself orbiting near the North Pole in a new B-52H with a crew of six.

They were the best crew in the wing, just a joy to be with. These guys were geniuses and amazing people. We carried four 1.1 megaton drogue retarded nuclear weapons to be dropped in a 53-second trail on a target on our maps labeled “Government Control Center.” I was 23 years old but was trained in the highly classified countermeasures that could shut down the electronic spectrum and penetrate the Soviet defenses around our target… Moscow. We continued to orbit while awaiting a launch “GO” code. Each day, after 12 hours orbiting with no horizon, in a sky that was as bright white as the inside of a milk bottle, another B-52 relieved us to maintain this position in “white space”. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, our orbits near the North Pole went on for 45 days.

On one of these flights, a US Senator who was visiting our Headquarters the Strategic Air Command (SAC) asked to speak to someone in an aircraft that was on “airborne alert”. I was voted to be the one to take the call on my 1000W HF radio and I was eager to do it. “How you boys doing?”, he asked in a Southern accent. The crew was urging me to tell him to go f*** himself and worse, so my answer probably stunned him… “We just had turkey dinner we’re doing great!”

During this time, I knew the enormity of what we were involved in. We were impervious and our crew understood that “we could evaporate a city of 20 million followed by a full-blown Nuclear War”. This was our only mission, and our Radar Navigator William R. Gilmore (USNA ‘59) could find a missile silo in a haystack. His pinpoint bombing accuracy allowed many of his B-47 and later B-52 crews to get “spot promotions”. We had trinkets in our survival kits (including gold pieces) for bartering our way out in the event of capture. We were armed with a handgun and a silk “blood chit”* that read “I am an American Serviceman, help me and you will be rewarded.”

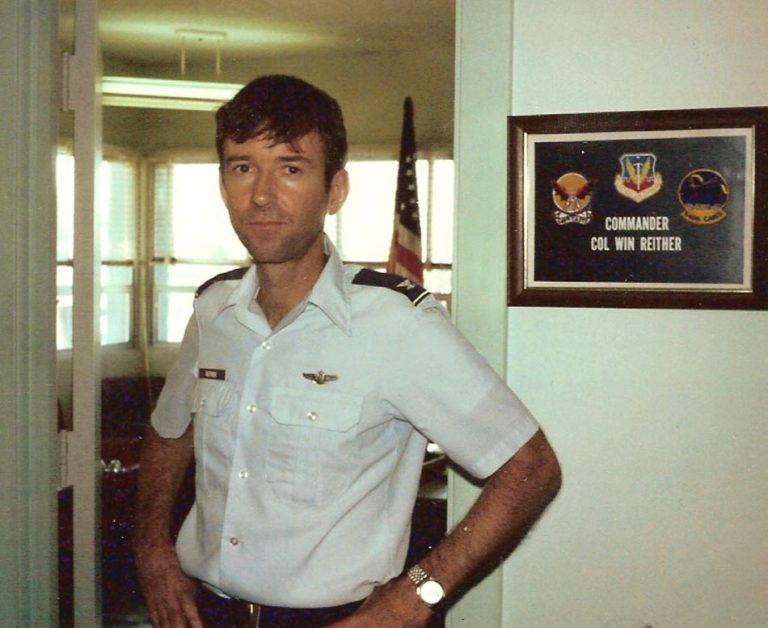

Fortunately, the “GO” code never came, the USSR had blinked and we stopped these 24-hour flights. My last flying job was at Patrick AFB as Group Commander, training all Air Force Forward Air Controllers to fly the O-2 Skymaster and the 0V-10 Bronco. My last military assignments were in the Pentagon as an Air Force Division Chief and later after Reagan was elected, as an Air Force spy in the “Office of Secretary of Defense” where I advised General Mike Loh of civilian micro-management initiatives. The Munitions budget programs I managed went from $1.5B to $11.7B in five years and I acted as the munitions panel chairman

Civilian Life

I left the USAF at age 46 and worked for LTV Aerospace/Control Data, at Grumman’s Washington, DC office advocating LTV’s A-7F prototype, Control Data Cyber Computers, and after the merger with Northrop Grumman’s Joint Stars, and F-15 EW programs until 1998. I started a Political Action Committee, VetsPac PAC, lobbying the Armed Services Committees to better support combat-injured Veterans. In 2004 I successfully sponsored Armed Services Committee Authorization language that increased Concurrent Retirement and Disability Pay. Currently, I assist SSS members suffering from Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), a type of lung disease associated with flying the F-100.

Win Reither is currently the CIO for the Super Sabre Society.