Ron Standerfer was born and raised in Belleville, Illinois, a town across the Mississippi river from St. Louis, Missouri. While attending the University of Illinois he took his first airplane ride in a World War II-Vintage B-25 bomber assigned to the local ROTC detachment. It was a defining moment in his life. Weeks later, he left college to enlist in the Air Force’s aviation cadet program. He graduated from flight training at the age of twenty and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant.

Another defining moment occurred early in his career. In August 1957, he participated in an atomic test at Yucca Flat, Nevada. Standing on an observation platform eight miles from ground zero, he watched the detonation of an atomic bomb code-named Smoky. The test yielded an unexpected 44 kilotons—more than twice the size of the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. He never forgot Smoky, and the memory of that experience weighed heavily on his mind when he wrote The Eagle’s Last Flight, a semi-autobiographical novel about his life as an Air Force fighter pilot during the Cold War.

Ron’s twenty-seven-year Air Force career spanned the Cold War years between 1954 and 1981. During that time, he flew a variety of high-performance fighters including the F-100, F-102, F-105, F-4, and A-7. He flew over 200 combat missions during the Vietnam conflict and was awarded two Silver Stars, thirteen Air Medals, and the Purple Heart. The latter was received after he was shot down over Tchepone, Laos in 1969. He retired from the Air Force just as the Cold War ended as a full Colonel after tours in the Pentagon and Tactical Air Command headquarters in Virginia.

He continued to pursue his passion for aviation after retiring. He was a marketing director for Falcon Jet Corporation, a subsidiary of the French aerospace manufacturer Dassault Aviation. In that capacity, he was responsible for launching the marketing campaign for the Falcon 900, a long-range business jet. Later, he was the owner of an aircraft charter and management company in Elmira, NY, and also a marketing consultant.

Ron is a prolific writer and journalist. He appeared on WOR-TV in New York City during the first days of the Persian Gulf War, providing real-time analysis of the air war as it progressed. His book reviews and syndicated news articles are published regularly in the online and print news media, as well as in military journals.

These days Ron and his wife Marzenna, the daughter of a distinguished theatrical family in Poland, spend their time in their homes in Gulf Stream, Florida and Warsaw. (1)

His recent book, The Eagle’s Last Flight (www.theeagleslastflight.com), chronicles the life of an F-100 pilot and his family during the Cold War and Vietnam years. (2)

Source: (1) Amazon.com: Ron Standerfer: Books, Biography, Blog, Audiobooks, Kindle; (2) Mistyvietnam.com

Ron Standerfer – Caterpillar Club

My Two Ejections

My Two Ejections

My first ejection was in 1962. Dave Moseby and I were ferrying two birds from Misawa to the alert pad, which was at Osan AB, Korea, at the time. We needed to burn off some fuel when we arrived, so Dave put me in the trail position, headed for the deck, and started a loop. I was having a great time, sticking to him like glue. Then things fell apart. Just before the top of the loop, I eased back on the stick to move in closer. Nothing happened. As Dave started to disappear above my head I eased the stick back further. It was frozen. I had no flight controls and was flying straight up! The big question was what the aircraft would do when the airspeed reached zero. I figured if it rolled inverted and fell toward the horizon, I might be able to roll it upright with the rudders and eject.

But the aircraft did not roll toward the horizon. When the airspeed reached zero, it began to buck and shake violently. Then, it tried to nose over to the straight and level, upright position. Too late, I realized that my lap belt was loose. Rendered weightless by the negative Gs, I floated out of the seat, along with every loose item in the cockpit. My head and shoulders were jammed against the canopy, arms pinned against the windscreen. The cockpit was filled with debris, all at the top of the canopy with me. A navigation book floated up and struck me in the head, cracking the sun visor on my helmet. I tried to free my hands so I could find something to hold on to and push myself back into the seat, but the G forces wouldn’t let me.

Without warning, the aircraft rolled over and snapped into a tight inverted spin. I could see the rice paddies rotating faster and faster as the spin tightened. It was time to go, even though it meant ejecting inverted. The thought crossed my mind that I would no doubt be severely injured in the ejection because I wasn’t fully in the seat, but it didn’t matter. It was better to be injured than to die. I managed to free my left arm from the top of the canopy, reach across my lap and raise the right ejection seat handle. It was an awkward maneuver, but somehow I did it. The canopy departed the aircraft with a loud bang, as onrushing air jammed me back into the seat and swept all the loose items out of the aircraft. I squeezed the exposed trigger and was gone.

The chute opened normally and after a minute or so I realized I was unhurt. So far so good. Then I saw the river, snaking through the rice paddies like a fat muddy serpent, looking as wide as the Mississippi. I’m not much of a swimmer so I decided to deploy the life raft in my seat pack and inflate my under arm life preserver. That way I would be ready, no matter how deep the river was.

The river was only three feet deep. The impact of my fall drove me another foot into the muddy bottom. I tried to stand up but the weight of my survival equipment pulled me backwards causing me to plop unceremoniously into the water. It was a ludicrous sight, me sitting knee-deep in water surrounded by my survival equipment. The bright yellow one-man life raft floated nearby, clearly not needed, while my parachute canopy with its alternating orange and white panels had collapsed a few yards away. But the piece de resistance was my fully inflated, DayGlo orange life preserver, which remained high and dry because the water was so shallow. A little Korean boy ran to the river breathlessly, his mouth agape, marveling at the scene before him. I looked at him and then at the colorful collage of unneeded survival equipment that surrounded me and began to laugh. When I did, the little boy laughed too, although he didn’t know why. Finally I got to my feet and waded to shore. The little boy helped me drag my parachute to higher ground.

The news traveled quickly to Misawa. Ejections were common in those days, but landing in three feet of water with full sea survival gear deployed? It was priceless! My squadron mates from the 531st teased me for months and many suggested that I was an ideal candidate to teach in the sea survival school at Numazu. It was a story that followed me for years.

The second time I ejected was on April 1, 1969, while I was flying a Misty mission. The late Lacey Veach (RIP) and I were putting an airstrike in on an interdiction point near Tchepone, Laos. There was a ZPU firing at us from a couple of clicks away but he wasn’t getting very close. In fact, I remember commenting when we pulled off from the final pass that the gunner definitely needed more training. Five minutes, later the “Engine Oil Overheated” light came on. I had never seen one ON before and had to look it up in the emergency procedures check list. It said to check the oil pressure. I did, and it was dropping. “No sweat,” I told Lacey, “they told us at Luke that jet engines sometimes run an hour or more without a drop of oil.”

The guys at Luke were wrong. Ten minutes later, as we were climbing through twenty thousand feet, the engine came unglued with a spectacular display of violent compressor stalls and gray smoke streaming into the cockpit. We were eighty miles west of Da Nang at that time and not far from the A Shau Valley. In other words — in the middle of nowhere.

There were four F-4s on our wing when we punched out. The ejection went okay—-perhaps a little easier than the one in Korea. But instead of a soft, shallow river to greet me when I landed, I crashed into the top of a very tall tree, atop a small mountain. For a moment it looked like I would be able to stay there, but it was not to be. After a moment or two of thrashing, slipping and sliding, I fell headfirst all the way to the bottom smashing into every branch and limb along the way.

The RESCAP didn’t get off to a very good start. The F-4s went off to hit a tanker and brought the rescue force back to a different mountain sixty miles away. It took nearly an hour to sort all that out. Meanwhile, Lacey and I were sweating it out because it was getting dark and we didn’t want to spend the night in Laos. Nobody did in those days.

When the rescue force finally arrived, the Spads got right down to business and located me in about ten minutes, despite the fact that I was concealed under multiple layers of trees. The pickup by the Jolly Green helicopter also went well, although my head got stuck in the fork of a large limb as I was ascending and they had to pull me and the limb loose by brute force, which wasn’t fun. It was worth it though.

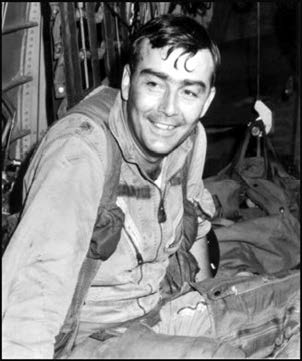

As luck would have it there was a USAF combat photographer on board the helicopter. He took the enclosed picture just minutes after I was pulled aboard. The big grin on my face tells it all!

Anyone interested in further details about these ejections can read about them in my book, The Eagle’s Last Flight. Although the book is classified as historical fiction it is very autobiographical in some parts.

~ Ron Standerfer