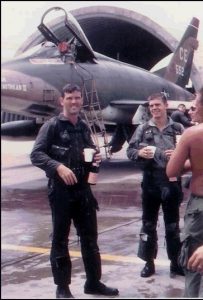

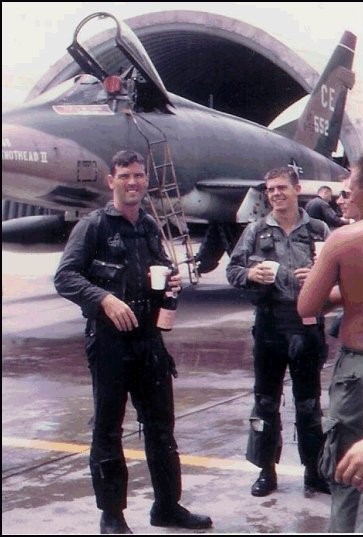

Born 1942. Grew up in Roxana, IL. Bradley University 1960-1964. B.S. Mathematics. Joined Missouri ANG as pilot trainee January 1965. Graduated UPT December 1966. Graduated F-100 check out, Luke AFB August 1967. Graduated U.S. Army Jump School, Ft. Benning July 1968. Voluntary combat tour 510th TFS, Bien Hoa, RVN, 1969. Two ferry flights of refurbished F-100Cs from “Bone Yard” to Turkey, 1972. Injured June 1973 while ejecting from a burning F-100D. Medically retired as a Captain. Currently living in Carmel, IN.

John C. Donham

At 09:56:50 hrs on June 9, 1973, my wing-man and I lifted off runway 30L at Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri, and began a climbing left turn. In the climbing turn, the morning sun played across the instrument panel. As the sunlight moved off, I saw the “FIRE” warning light illuminated. At 0958:25 I told Two I was coming out of burner and spread it out. I pulled the throttle inboard and back to idle, then told Two, “Check me over, I got a fire light”. Two confirmed, “Beautiful flames trickling out the aft end and smoke and flames from the bottom breather ports.”

At 09:56:50 hrs on June 9, 1973, my wing-man and I lifted off runway 30L at Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri, and began a climbing left turn. In the climbing turn, the morning sun played across the instrument panel. As the sunlight moved off, I saw the “FIRE” warning light illuminated. At 0958:25 I told Two I was coming out of burner and spread it out. I pulled the throttle inboard and back to idle, then told Two, “Check me over, I got a fire light”. Two confirmed, “Beautiful flames trickling out the aft end and smoke and flames from the bottom breather ports.”

I briefly considered trying to set her back down but rejected that idea immediately because of the fear the controls would become useless over the densely populated area. So I reversed my turn back towards an uninhabited area surrounding the Missouri River southwest of the metro area, continued trading airspeed for altitude, and settled into an idle descent.

We descended towards the river holding about 300 KIAS. Fuel flow was fluctuating and out of the corner of my eye, I saw one gauge suddenly plunge to zero (probably the utility hydraulic pressure). As we arrived over the river bottom area, Two warned, “It’s getting worse John, I think you oughta get out pretty quick”. I said, “OK, I’m leaving”.

I recall looking around the cockpit one last time and getting a guilty feeling, “This is all wrong! If I jump, she’ll crash!” But fire can be highly motivating. I pulled the nose up, raised the left armrest partially, then let go of the stick, grabbed the right armrest and yanked. It seemed to take way too long for the canopy to blow off but it finally did and I found myself whistling through space. Two radioed Departure I was out and had a good chute. The time was 0959:35. The aircraft pitched over and went straight in, hitting dead center in the middle of the river. It exploded on impact and the swiftly moving river swept the small pieces downstream. They estimate the engine probably went to a depth of 30 feet below the channel bed. With the exception of me, the seat, canopy and a piece of the skin about the size of a serving platter, none of F-100D #55-2947 was recovered.

F-100D #55-2947 sported the new “Directional Automatic Realignment of Trajectory (DART)” ejection system coupled with a ballistically spread parachute. The seat was to remain tethered to the aircraft by a cable. It didn’t. The purpose of the ballistically spread chute was to bring the pilot to a more abrupt stop. It did. The opening shock peeled my helmet and gloves off and sheared the antenna off the survival beeper radio. The top part of my clipboard separated and several risers were frayed – but held. I suffered a broken shoulder and a spinal injury that paralyzed my left arm. After regaining consciousness, I tried to check my chute but could not rotate my head to look up. I stared down between my boots to see I was descending towards a fast-moving Missouri river well above flood stage. With just one good arm and no water-wings, I foresaw a bad day getting even worse.

I didn’t know it at the time but along with my spinal cord injury, the brachial plexus artery in my left arm had been pulled in half. Although I was pumping blood into all the nooks and crannies of my chest cavity, God was with me that morning. While my left shoulder and upper arm were shattered, no bone fragments pierced the skin. Had they, I would’ve bled out on the way down. With really low blood pressure, I just could not remain conscious, try as I might. I’d pass out, then wake up. I kept struggling to remain awake because I knew if I went into the river I’d need to dump the chute immediately if I was to have any chance. That was the only time I was scared that morning. But fear can’t trump really low blood pressure and I finally went out like a light and stayed out for the rest of the decent.

Fortunately, God continued to watch over me that morning. A westerly wind blew me back over land and I came down in a wooded area not far from the river. Although I entered the woods hanging unconscious in my chute, legs apart, no helmet and face down, I penetrated all the way to the ground without getting skewered by an Oak limb. Even the impact with the ground was soft as my chute entangled to leave me with just enough riser to slow almost to a stop before hitting the ground.

Two buzzed me as I crawled out of my chute harness. I felt nauseous, hot, thirsty, and confused. I could not raise my head without using my right hand to move it. A helicopter arrived and took up station overhead. A deputy sheriff arrived, checked me over, and headed back to his patrol car to direct an ambulance to the scene. I was really hurting and decided not to wait for them to get back to my location. With the help of a civilian who’d watched me descend, I got to my feet, unzipped my flight suit partway, put my left arm inside for support and started walking out. We reached a hiking trail through the woods and started down it towards the road. But we came upon a large Sycamore tree that lay across the path. I just could not get my leg up over it so I laid down to await the paramedics.

– John C. Donham