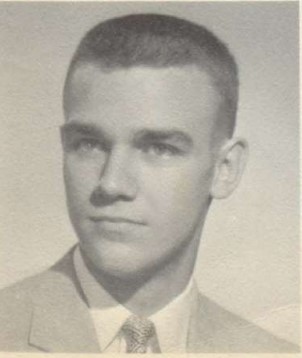

First Lieutenant William Barriere received his commission in 1962 upon graduation from Newark College of Engineering

where he also received a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering. He was then assigned to Craig AFB for Pilot Training and received

his advanced fighter training in the F-100 at Luke AFB. Bill is assigned to the 429th FFS, Cannon AFB, and in 2007 was TDY in

SEA. He has logged over 350 hours in the F-100.

“I was quite unhappy about the whole situation!”

Out of the Pan, Into the Fire.

By William Barriere

Just the thought of stepping over the side is at best— frightening. Couple it with a sick F-100, the black of night and a thunderstorm, with unfriendly types in the area, and it turns into a terrifying experience.

However, the most disconcerting part of the entire episode was when I pressed the mike button and heard myself say, “I’m climbing for altitude to punch out!”

It all started when I was flying wing position during the final approach phase of a TACAN approach. My first indication that something was amiss was when I heard Lead call, “Pull up.” At this point the aircraft began bumping and buffeting, and I had to use full control to keep the aircraft straight. I thought I saw Lead’s AB light, so I lit mine. I had hit something extremely hard with my right wing and the aircraft rolled to the right into a past- vertical bank of about 110 degrees. I thought about punching out right then, but decided against it because I was too low and practically upside down. I had full left rudder when the AB cut in and kicked the nose back up. I just snatched back on the stick and the wings rolled level—I was up and out of the trees. As fate would have it, I now had a chance to bail out under more favorable conditions (I thought). I was out of the frying pan, but soon to be in the fire!

I caught sight of the field through the driving rain as I started a circling climb for altitude. The fuel was dwindling rapidly and I wasn’t sure of the exact amount because only the forward gauge was readable. I came out of AB with approximately 500 pounds remaining and started to position the aircraft for ejection over the runway. (There were unfriendly types in the area and I thought the safest place to leap out would be over the base.) During the climb, I stowed all the loose equipment in the cockpit (checklist, maps, flashlight, etc.). I wanted to be sure nothing would bind the seat when I went out.

I had to use left stick because of wing damage, and one tank was bent considerably. I zoomed the aircraft to about 140 knots and dropped the left wing 30 degrees. (I couldn’t trim out the roll, and I hoped the wings would be rolling through level when I ejected). It took one continuous movement to release the controls, assume seat position, grasp the unlocks, and raise the handles. Then things got tense.

When the canopy jettisoned, the 140-knot wind hit me in the face and my thought processes were immediately arrested. I had practiced countless times in the seat trainer how I would reach from the handles down to the exposed triggers. Nevertheless, I squeezed the unlock levers twice before realizing they were not the triggers. Shocked back to reality, I immediately slid my hands down and found the triggers. The idea of hanging on to the seat for dear life had bugged me before—so I reached down, put my fingers on the triggers and raised them with my hands still open (fist not clenched). That way I couldn’t possibly have hung on to the seat.

The rocket blast was a terrific shock. I felt crushed down into the seat with considerable force and had the feeling of tumbling forward like a pinwheel. The windblast and buffeting were quite violent, and my mask went from my chin to my forehead before it stopped. The buffeting quit suddenly (at seat separation, I assume). I threw out my arms and legs to stabilize and reached for the “D” ring. At that instant I felt three quick tugs and the chute blossomed. There was no “opening shock” to speak of—just a mild deceleration. The chute looked mighty fine. After releasing one side of the mask and deploying the survival kit, the sickening swaying motion stopped and the chute was pretty stable.

I had punched out at about 6,000 feet and could see the area quite well, even through the heavy rain. The field was directly under me and a battle was raging to the southeast. The mortars and small arms fire were clearly distinguishable, and parachute flares were being dropped in the area.

Looking straight down was quite startling. The wind was blowing about 30 knots and carrying me directly toward the firefight that was unfolding in the distance. I tried to climb the risers and slip the chute back toward the base, but my 140 pounds didn’t seem to tip that bear very much. After a few more futile attempts, I resigned myself to the fact that I was going “anyway the wind blew” and started to concentrate on making a good landing.

The firefight was very nearby now, and the flares lit the terrain well. I was relieved to see the area was flat with low bushes, so all I had to do was hit the ground with some semblance of order. I unsnapped my canopy safety covers and kept making body turns to face where I was going. Just before impact, I re- hooked my oxygen mask to protect my face from the bushes.

I hit very easily next to a large bush, and my PLF rolled me into it. A short tug on the harness told me the chute was still inflated, so I hooked my thumbs in the rings and pulled; they released immediately. (I always had trouble practicing with the old release, but found the new ring types extremely simple to find and actuate).

The immediate area was well lighted by mortar flares, and the shooting was close by. I was quite unhappy about the whole situation, so I crawled into the middle of the largest bush I could find. (I looked around for the canopy in an effort to hide it, but to no avail. I found out later that it blew away about one fourth of a mile.) I unsnapped the holster on my .38, found the lanyard on the survival pack and started to pull the kit to me. It got pretty crowded in that bush when I finally got the one-man dinghy and survival kit in there.

The parachute harness had done its job, and after I located the kit, I slipped out of the harness. Without the flares directly overhead, it was black as pitch, and I spent quite a while fumbling around inside the kit feeling for something like a radio. (It would be smart money to know what your particular kit contains and how everything is packaged, so if you stow your flashlight like I did, you could still find what you were looking for.) I pulled out the largest sealed package I could find and tried to tear it open. I ended up using the hook blade knife. The radio and battery were hooked up, so I extended the antenna and started to transmit tone.

The choppers were already in the area and lowered their lights to see through the heavy rain. I don’t see how they avoided being hit by small arms fire. I took my helmet off and tried to transmit voice without success. When the choppers got in close, I held a steady tone. Within about one fourth mile their search pattern became very erratic, and I thought my radio was faulty. I made several attempts to dry off the antenna, and I put the battery inside my flying suit to keep it dry (I learned later from the chopper pilot that the URT-21 beacon in my chute was overriding my URC-11 survival radio. I should have turned off the beacon in my chute before using the URC-11 for homing.) I hesitated shooting a signal flare for fear some undesirables would see it and get to me before the choppers could.

The flares started dropping again and small-arms fire was getting quite close. A mortar shell hit about 50 yards from me, and I figured it was a good time to leave my position. I put my helmet back on (it’s a fine substitute for sound suppression) and took the radio with me. I started to move back in the general direction of the base and used the radio to transmit all the while. I traveled about half a mile and saw a chopper set a course that would intercept my path about 40 yards in front of me. When he was about one-fourth mile away, I started to run, and his lights caught me just before I reached him.

He set the chopper down directly in front of me, and I was conscious of being silhouetted in those bright lights. The wash from the rotors almost blew me over, but I held my position while one troop jumped from the chopper (to cover me with an AR-15) and another led me aboard. (I was hesitant to run up to the chopper for fear of getting hit by the rotors.) I was never so happy to see anyone in my life, and my first chopper ride turned out to be an extremely delightful experience.

I gained enough experience in one evening to last for a while. I think my outlook now goes something like this:

“When things are looking bad, don’t worry… ‘cause in a few more minutes, things could really get hairy!”