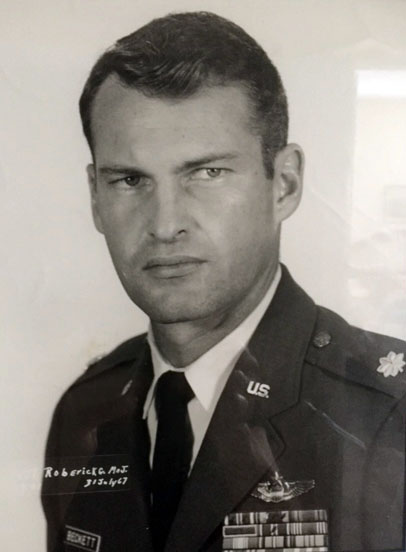

I LIVED TWO LIVES: the first with the Air Force, the second with Flight Systems Inc. by Rod Beckett

Rod Beckett had a successful flying career with the Air Force, from cadet days in 1956, until retirement at Holloman in August 1976 when he took up farming. “Farming is, well, farming, but for me, there was something missing in my life. At first, I couldn’t exactly put my finger on it. But, in the back of my Aviation Cadet mind, I knew it was the lure of the cockpit, the absence of “laughter-silvered wings,” and this reality was heartbreaking!

A PROVIDENTIAL JOB OPPORTUNITY

About a year after retiring, one morning in the fall of 1977, Carol and I were looking into our moneybag and found it was being rapidly depleted. With bills to pay and three children to send to college, we were beginning to have doubts about our financial future.

Also, the reality had hit me that I might never fly again! This possibility caused extreme angst and affected my disposition to the point I told Carol I needed to get a flying job. She simply said, “You better start making some telephone calls.”

Before I could get my thoughts together as to whom I might call about getting a flying job, I got a phone call the very next day from Zack Haynes. I had only casually known Zack while we were both still on active duty at Holloman.

I was somewhat surprised at this call out of the blue, and flabbergasted when, after some small talk, he asked if I might be interested in a job flying F-86s and T- 33s at White Sands Missile Range (WSMR, pronounced Whizmer), “and you wouldn’t even have to move!”

“You bet, Zack,” I replied without hesitation, “Sign me up.”

Zack’s job was operating FSI T-33s out of El Paso International Airport under an Army Air Defense Command services contract to tow banner targets for units training on the Vulcan cannon. He said that when he got word that FSI was looking for a pilot to head up a new contract/project with the U.S. Army at WSMR, he thought of me immediately and hence his first call to me.

FSI had responded quickly and positively to Zack’s recommendation of me and told Zack to tell me to submit my resume, from enlistment in the Air Force until retirement, and to include jobs thereafter to the present day. When Zack reviewed my resume before sending it on to FSI, he suggested I change my last job listed as “farmer” to something a little more sophisticated, like “engaged in agriculture,” which I did.

I guess that did the trick because not long after that, I was invited to interview with an FSI executive at a meeting in Las Cruces, NM. There, I learned that the company had recently won a contract with the U.S. Army Targets Office in Huntsville, AL, to “drone” (strange new terminology, meaning “to convert to a drone”) 21 F-86s to QF-86s and operate them on WSMR as targets to test the new Patriot missile system, then in development.

FSI was looking for someone with my experience (including maintenance, aha!) to run this new program out of an office they had secured at Holloman. My immediate task would be to hire 20 experienced people, including pilots and maintainers, to man this operation. I told the interviewer that I knew very little about drones but was a fast learner and sure I could do a good job for them. A couple of days later, I had a job offer with a salary almost equivalent to what I was making before I retired…

I went to work for FSI in October 1977. The only problem was that the job was only guaranteed for a year and a half, as I found typical in civilian land; just the length of the current contract. But as it turned out, the full- time job with FSI was to last 20 wonderful years! That first QF-86 target drone services contract I led for FSI grew, changed and lasted many years. And, because I was in the right place at the right time, FSI nabbed another lucrative contract at Holloman, i.e., FSI’s first F-86 Sabre dart-tow program that got started to support the F-15’s arrival there.

..FSI was a great company to work for, growing swiftly, and I came to love Bob Laidlaw like a brother. During my work with Bob in the early days of FSI, he once told me that, “You can’t pull a rabbit out of a hat unless you first put a rabbit in the hat.” This became the “Laidlaw Doctrine” to me, and I saw it in action many times during my years with FSI.

I had heard that Bob had leased a couple of F-100s (one D- and one F-model) from the USAF to use in FSI business at their home base of Mohave Airport, CA, to flight test/certify certain systems for contractors doing business with the Air Force.

One day in January of 1979 while I was at Mojave to pick up a QF- 86 to ferry back to Holloman, Bob asked me if I would like to go to Europe with him to pick up some F-100s he was considering purchasing in Denmark. I told Bob I would love to do that, but that I hadn’t flown the Hun for 16 years (’63-’79) when I rode in the back seat of an F-100F giving a guy a re-currency check.

I told him I’d need a trip around the pattern to get recurrent. Bob said he could arrange that, when and if he managed to acquire the Danish Huns. That took some time, but by August 1982 he had pulled it off. In effect, he was putting 6 rabbits into a hat!

True to his promise, Bob then arranged for Ted Sturmthal, one of his test pilots, to check me out in the leased F-100F on 25 August of that year. After a review of the Dash 1 and some cockpit time, things began to look familiar. Ted and I cranked up and flew over to Edwards AFB, where we shot touch-and-go landings on their long runway. After about two touch-and-goes, Ted decided I was good to go, and we went back and landed at Mohave. Ted then made an entry in my logbook, and there I was, recurrent in the Hun after 19 years (’63-’82)!

THE PURCHASE PICKUP

By November, it was time to go to Karup Air Base, Denmark, where Bob Laidlaw, Ken Coffee (another Hun-qualified FSI pilot), and I would pick up the six Danish Huns. Due to some necessary international diplomatic maneuvering by the U.S. State Department, three airplanes would go temporarily to Bitburg Air Base, Germany, and three airplanes would go temporarily to Spangdahlem Air Base, Germany, to await arrangements for an FSI maintenance facility in England to be completed. Bob had already sent a cadre of about four F-100 mechanics over to Karup to go through the airplanes and check out all the systems to ensure they were ready to fly.

When we got there, the maintenance crew met us in the hotel bar to brief us on the condition of the six airplanes. Bottom line: the birds were in very good condition, but well overdue major inspections and preventative maintenance; and that the long pole in the tent (for ferrying the airplanes) was the dependability of the radios.

We decided that since the weather at Karup was forecast to be good for several days, the prudent thing for us to do was to take three of the Huns with the best radios and fly them around the flagpole a few times. Bob led that local flight gaggle on 15 November. I think the only write- up we had on the three airplanes was a single minor radio problem.

On 17 November, we took the first three Huns to Bitburg Air Base. I led that and subsequent cross-country The FSI mechanics had inspected the six Danish Huns at Karup Air Base and briefed their findings to the pilots: All “in very good condition.

At this point, we knew we had three good radios in the birds at Bitburg, but the radios of the three still at Karup were highly questionable. So, we had our maintenance guys take those good radios out, and we put them in our parachute bags, returned to Karup by commercial air, and had the three working radios installed in the remaining three airplanes.

While en route back to Karup, the three of us mutually agreed that with the weather forecast in Karup going sour quickly, we would blow off the flagpole circus on the remaining three airplanes and just take them to Spangdahlem without a shake-down flight. Back at Karup, we briefed our flight at the hotel bar the night before (which seemed to become our custom).

The weather forecast for our arrival at Spangdahlem on 18 November was not quite as favorable as Bitburg had been, so we planned to shoot the TACAN approach. Ken wanted to penetrate on my wing, but I vetoed that idea since it had been so long since I had flown the Hun in weather. I needed to concentrate on getting myself on the ground without having to worry about a wingman!

Sure enough, upon our arrival at Spangdahlem, it was snowing and the wind was blowing hard. (For those of you who have not flown out of Spangdahlem, there is a ravine at the approach end of the runway that caused it to get pretty rough when the wind blew.) I broke out slightly to the right of the runway centerline and did a little “rat’s ass” to the left that lined me up okay. I planted the airplane firmly on the numbers and thought, “Thank God Ken was not on my wing.” I would have lost him for sure, and I would not have wanted anyone to witness that exercise!

With all six FSI F-100s temporarily bedded down at USAFE bases on the continent, the three of us FSI “Hun drivers” flew back to our respective Stateside homes for the holidays, and to await completion of the negotiations for that maintenance facility in England.

It turned out to be at the Hurn Airport in Bournemouth, Dorset, near the south coast of England. The short length of the runway (6,000 feet, but near sea level) presented a few logistical and aeronautical challenges to come. But, we had plenty of time to work out the procedural solutions.

The original plan for the ferry flights from Bitburg and Spangdahlem to our new maintenance facility was to fly each set of Huns from the continent directly to Hurn. But given the marginal climate factors prevalent at the time of year we planned to do the ferry flights, we assumed we would have to arrive at Hurn with enough fuel to fly to a suitable alternative. That put us at the mercy of the weather because, due to the short Hurn runway with no barrier, we wanted to land with a fairly light fuel load.

The solution was to do the ferry flights in two steps, the first to Bristol airport, about 60 miles northwest of Hurn. Then, whenever we had VFR weather, we could safely hop on down to Hurn with internal fuel only—light enough to land safely on the 6,000-foot runway.

Bob made the arrangements for us to use a Flight Refueling Ltd. facility at Bristol, and with this plan, Bob, Ken, and I flew back to Europe in mid-January of 1983. We ferried the three Huns from Bitburg to Bristol on 23 January, returned to Spangdahlam, and ferried those three Huns to Bristol on 28 January.

Things went as planned and with good weather, we took all six birds into Hurn on 1 February. Flight Refueling Ltd. (FR for short) was the company Bob had contracted with to provide hangar and shop facilities where, with our mechanics doing the work, we would accomplish the needed inspections and repairs as necessary (similar to the familiar IRAN process) for these six initial FSI F-100s in Europe.

With the six “rabbits” in the hat for IRAN, the three of us headed back to the States while our mechanics got to work. Because of the F-86 target tow program, now rolling into high gear, I had become CINC Tow for Flight Systems, Inc.! [Officially, Manager Fight Operations, Flight Systems, Inc., Holloman AFB, New Mexico.]

The “Deci” Connection As part of the IRAN, FR stripped the Danish camouflage paint, repainted with the Flight Systems colors—white with a blue stripe—and added the new U.S. aircraft numbers provided by the FAA European rep, in the form of “NXXXFS.” Altogether, they were beautiful! (One of the things I always respected about Bob Laidlaw was that he loved airplanes as much as I did, and he insisted that they always looked good and functioned as well as they looked. Additionally, Bob took good care of the people who flew and maintained his airplanes.)

We were on a roll! In early March of 1983, as FSI’s CINC Tow, I took one of my mechanics and one of my pilots from Holloman to Decimomannu Air Base on the island of Sardinia, Italy, where we would receive support equipment, tools, and three additional mechanics from Mojave to start up the contracted Dart Tow program for USAFE. The contract required us to have three operational F-100s in place at “Deci” to officially begin the program.

All we had to do was pull three of the “rabbits” out of the hat at Hurn, when each was ready for and passed a Functional Check Flight (FCF), and release them for contract work. The process we developed to ready the “rabbits” was this: when an airplane was ready to FCF, the FSI maintenance supervisor at Hurn would notify me at Deci. I would leave Deci on Friday afternoon on a commercial flight from Cagliari, usually through Rome or Milan, to London and then rent a car. I would then drive to Bournemouth, check into a hotel, and have dinner with the maintenance guys, who would brief me on the airplane ready for FCF. We would agree on a time to arrive at Hurn to FCF the airplane(s). Sometimes the FCF would be delayed or the bird didn’t pass. The first airplane I released after passing the FCF was N415FS. That was on 20 March 1983. En route to Deci at last.

I had long wondered how a civilian could get a civilian fighter-type airplane out of England and across France to Italy, without getting arrested! I had previously counseled with some of the FR pilots. They told me it was simple. “Just file an ICAO flight plan the day before my planned departure, and the British Air Traffic Control people would let me know that day if the French had accepted the flight plan for the next day.”

In the remarks section of the flight plan for taking this first released FSI F-100 to Deci, I requested an en-route climb on course, because I was a little concerned about having enough fuel to get all the way to Deci, the last leg being over water. But it seems there’s always a chance for a mix-up. Although the read-back of my flight plan was as filed, after I got airborne, the British controllers vectored me on an easterly heading from Hurn to climb to my assigned altitude. When I questioned them about my requested en route climb, I was told that as soon as I entered French airspace, the French controller would clear me to climb on course.

Finally reaching my assigned altitude, I was in and out of the weather. But for some unknown reason, the French controllers were constantly changing my route of flight, and with charts all around me and holding the stick between my knees, I was all over the sky.

I finally broke out into the clear and got the airplane settled down on altitude and heading.

Much relieved, I looked out the right side, and what to my wondering eyes did I see, but a French Air Force Mirage joined up in close formation on my wing. Remembering that there was an ICAO signal for “follow me and land immediately,” and not remembering what the signal was, I just stared at the Mirage pilot and gave him a sharp salute and a thumbs-up. He returned my salute and gave me a thumbs-up—then did a split S and departed—and I never saw him again. I breathed a sigh of relief and continued on my way.

My next concern was whether or not the Italians knew I was headed to Deci. It turned out that they did, and the remainder of the trip was uneventful. The next plane I released was N416FS, also in March 1983. Finally, I released the last jet for Deci, N414FS, on 16 April 1983. Altogether, it took eight weekends in a row, but we finally had the three pristine Hun tow-ships assembled at Deci and the USAFE Dart Tow program was officially “on.” We had fulfilled the “Laidlaw Doctrine” and pulled three rabbits out of a hat at Hurn!

On 19 July 1983, I checked out R.Y.Costain, and he took over leadership of the Hun dart-tow program at Deci, running it until sometime in 1984-85 when Jim Brasier relieved him. The Air Force subsequently canceled that USAFE program with FSI, but Jim managed to secure a follow-on contract with the German Air Force, towing targets out of Wittmund Air Base in Northern Germany over the North Sea, and additionally, again out of Deci.

EPILOGUE

In the ensuing years, FSI kept me happily and gainfully employed with the Army QF-86 program (which by this time had become an Air Force program as well) and the F-86 Dart Tow program, which grew by leaps and bounds into a “really big show.”

An additional duty was to help out Zack with his T-33 tow operation at El Paso. Another significant assignment, in May 1989, was to take the leased F-100F, which was air-refueling capable, to the Boeing plant in Wichita, Kansas. The contracted task was to conduct receiver evaluations of the Spanish tanker program. This was a contract Boeing had with the Spanish Air Force to convert 707s to probe and drogue tankers (similar to the KB-50 although with no tail drogue). This included several day and night hook-ups on each wing.

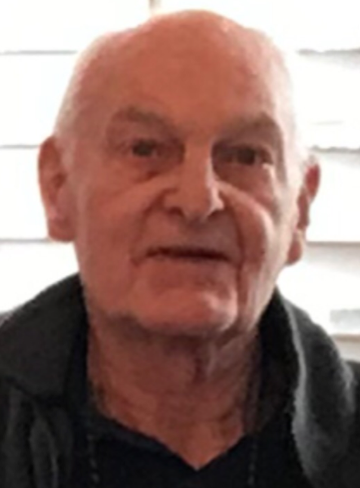

I retired from full-time FSI employment in 1997 with 20 years of service, but the Hun flying wasn’t completely over. I had, on occasion, several stints back in the cockpit as an independent contractor working for FSI. My final Hun flight with FSI was in June 2002 when I brought N418FS from Wittmund across the North Atlantic to Mojave, CA.

In my Air Force career, I flew 1,420 F-100 hours, and while working for FSI, I got an additional 1,872 hours in the Hun. That’s a total of 3,092 hours, thanks to Uncle Sam and Bob Laidlaw. What’s not to like about all of that?

After reviewing my Air Force Form 5 and civilian logbooks to put this chronicle together, I remain amazed at all of it. I am grateful to the good LORD that when He “wove me in my mother’s womb” (Psalm 139:13 NASB), He used the pattern of a fighter pilot and gave me opportunities to apply my trade, both in the U.S. Air Force and in civilian life, serving both God and Country.”

After his 2nd retirement, Rod continued to fly Huns as an independent contractor on a variety of FSI projects.

(This story is excerpted from the original published in Vol.1 No 21 Spring 2013 Issue of the Intake and is Part II of Rod Beckett’s story.) Medley Gatewood says: Thanks to Rod (and his daughter, Cathy) for taking the time to document a lot of Hun history in this two-part series.)