In 1950 Forrest Fenn joined the military. He wanted to be a fighter pilot but wasn’t sure his mediocre academics would land him in pilot training. Pilots were typically the high achievers. “I told myself that if I was going to compete in that environment, I couldn’t do it intellectually, but I could out-hustle all these guys,” says Fenn.

Fenn was born August 22, 1930, in Temple, Texas, and graduated from Temple High School in 1947, after laying over a year to play basketball. He studied at Temple Junior College for a couple of years and joined the Air Force as a private on September 6, 1950. He graduated from Radar Mechanic School at Keesler AFB and was sent to Donaldson AFB in Greenville, SC where he made Buck Sergeant.

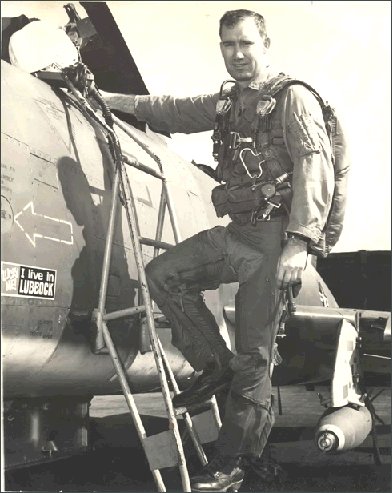

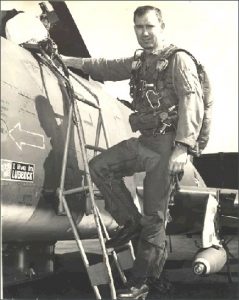

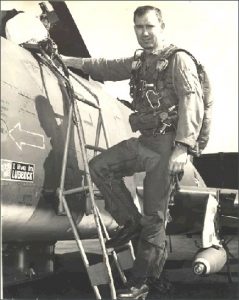

Sgt. Fenn then went to pilot training (Class 53G) at Bainbridge Air Base in GA, and Laredo, TX, where he flew the T-6, T-28, and T-33. After attending F-86D training school Fenn was assigned to the 85th FIS at Scott AFB, IL. Within a couple of years, he became aide-de-camp to M/G Frank H. Robinson who commanded the Crew Training AF at Randolph AFB, TX. He became a regular officer, flew the F-86D, F-86F, F-84G, F-89, T-33, F-100C, and graduated from the Army Helicopter School on the H-13G in 9 days. Aides could do that.

In 1957, Fenn was assigned to the 23rd Fighter Day Squadron (which would become the 23rd Fighter Bomber Squadron) at Bitburg, Germany, flying the F-100 C and F models.

In 1960, he returned to Luke to teach Gunnery School flying the F-100 C & F with squadrons 4511th and 4515th. On assignment for the Cuban Crisis, he began serving with the 4517th. Afterward he was off to Reese AFB, TX to teach pilot training flying the T-38.

His tour of duty in Vietnam began in early January 1968, and he tells 2 remarkable stories. “… I was sent to Tuy Hoa, Vietnam, where I ran the command post and flew 328 combat missions in 348 days. I was shot down twice. The first time I took battle damage and “dead-sticked” an F-100D model onto a 5000-foot runway. I took the chain going the wrong way but the aircraft stopped in 340 feet. Who said you need a long runway to stop the Hun?

The second time, I was shot down by ZPUs (towed anti-aircraft gun), ejected at Tchepone, Laos, and was picked up the next day by the famous rescue Jolly Green helicopter, “The Candy Ann”. For more of Fenn’s caterpillar story see: https://supersabresociety.com/caterpillar-club/forrest-fenn-caterpillar-club/

I returned to Reese to teach pilot training in the T-38 but the assignment was changed to the T-37 by the jerk DO. I turned down a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and retired.” Fenn retired with a cadre of medals for valor, but says the experience still haunts him. “I had this nightmare …where I was told that the government knew exactly how many enemy soldiers I killed, and they were going to tell me,” he said.

His time in the service led him to his life’s ambition. “Because I had a hard tour in Vietnam, I wanted the world to stop and let me out. If I have an advantage over everyone, it’s that I think a lot. I told myself that from now on, I was going to wake up at 7 in the morning, lay in bed till 8, and think.”

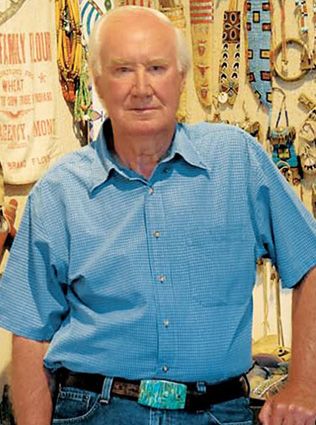

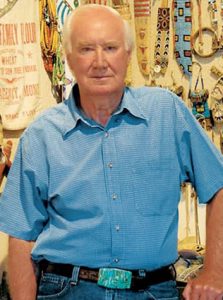

This “thinking time” got him motivated. He packed his family into the car and moved to New Mexico, where he built an art foundry and gallery. “Santa Fe was the only place I knew where I could wear Hush Puppies and blue jeans and make a living.”

Fenn bought a Navy T-28C (tail hook) out of mothballs in Tucson and restored it for fun. He also bought Rockwell Commander 112TC and a Piper Malibu for business. He put a turbine engine in the Malibu. When Forrest Fenn stopped flying he had 7,440 hours of time.

‘I sold my business after 17 years and retired to write 11 books on art, archaeology, ethnology, history, a few biographies, and 3 memoirs. At age 87, and 64 years of marriage, I’m resting with the devout understanding that making plans is antagonistic to freedom. Now, between naps, I sit and water my trees.”

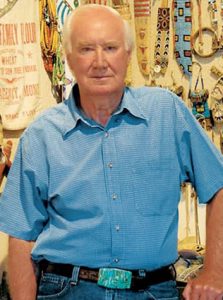

Forrest Fenn (Major, USAF Ret) “Headed West” on September 8, 2020

Forrest Fenn (Major, USAF Ret) “Headed West” on September 8, 2020

Forrest Fenn (90) passed away from natural causes in his home in Santa Fe, NM. Fenn was raised in Temple, TX, where his father was a school principal. He spent many summers with his family in Yellowstone National Park, the genesis of his appetite for adventure.

In 1950 Forrest Fenn joined the military. He wanted to be a fighter pilot but wasn’t sure his mediocre academics would land him in pilot training. Pilots were typically the high achievers. “I told myself that if I was going to compete in that environment, I couldn’t do it intellectually, but I could out-hustle all these guys,” says Fenn.

Fenn was born on August 22, 1930, in Temple, Texas, and graduated from Temple High School in 1947. He studied at Temple Junior College for a couple of years and joined the Air Force as a private on September 6, 1950. He graduated from Radar Mechanic School at Keesler AFB and was sent to Donaldson AFB in Greenville, SC where he made Buck Sergeant.

Sgt. Fenn then went to pilot training (Class 53G) at Bainbridge Air Base in GA, and Laredo, TX, where he flew the T-6, T-28, and T-33. After attending F-86D training school Fenn was assigned to the 85th FIS at Scott AFB, IL. Within a couple of years, he became aide-de-camp to M/G Frank H. Robinson who commanded the Crew Training AF at Randolph AFB, TX. He became a regular officer, flew the F-86D, F-86F, F-84G, F-89, T-33, F-100C, and graduated from the Army Helicopter School on the H-13G in 9 days. Aides could do that.

In 1957, Fenn was assigned to the 23rd Fighter Day Squadron (which would become the 23rd Fighter Bomber Squadron) at Bitburg, Germany, flying the F-100 C and F models.

In 1960, he returned to Luke to teach Gunnery School flying the F-100 C & F with squadrons 4511th and 4515th. On assignment for the Cuban Crisis, he began serving with the 4517th. Afterward, he was off to Reese AFB, TX to teach pilot training flying the T-38.

His tour of duty in Vietnam began in early January 1968, and he tells 2 remarkable stories. “… I was sent to Tuy Hoa, Vietnam, where I ran the command post and flew 328 combat missions in 348 days. I was shot down twice. The first time I took battle damage and “dead-sticked” an F-100D model onto a 5000-foot runway. I took the chain going the wrong way but the aircraft stopped in 340 feet. Who said you need a long runway to stop the Hun?

The second time, I was shot down by ZPUs (towed anti-aircraft gun), ejected at Tchepone, Laos, and was picked up the next day by the famous rescue Jolly Green helicopter, “The Candy Ann”.

Fenn returned to Reese to teach pilot training in the T-38 but the assignment was changed to the T-37. He turned down a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and retired.”

Fenn is survived by his wife Peggy of 66 years and his daughters Kelly and Zoe.

More information will be posted as it becomes available.

Unassing a C-model Near the DMZ

Unassing a C-model Near the DMZ

It was 1755L on December 20, 1968, when I floated down into the beautiful Laotian jungle near the DMZ. What a paradise! I had been leading a flight of four C-models out of Tuy Hoa on what was to be my last mission (number 327). Both my wingman and I had four CBU-34s and the other two had four M117s with instant fuses. Our mission was to mine the main trail at Tchepone, and we planned it for a late TOT to take advantage of the low sun.

My first pass was up the canyon, along the road and into the sun, 200′ and 500 knots, hoping to surprise the guns we knew were there. It took about ten seconds for the cluster bomblets to roll out of the canisters, so I was straight and level for a long time. I probably took hits on that pass. At the end of the run, I pulled up and came back out of the sun for the second pass expending both inboard CBU-34s.

Toward the end of the run, I saw multiple muzzle blasts at 11 o’clock and level with me. I think they were holding a couple of ZPUs steady so I could fly through the bullets. My first indication of trouble was when the canopy shattered and thick pieces of plastic hit my body and scarred my visor. Both drop tanks had ugly 50 caliber holes, fuel was pouring out (we had just exited a tanker), and the engine started going through withdrawal. It kept chugging and trying, so I felt it didn’t really want to quit. When it did, I knew my life was about to get exciting.

So I made a tight 270 to the right, heated the guns, and gave the NVA guys about 200 rounds of HEI. When I pulled up and looked back, they were still shooting.

Nail 74, (the FAC, Lt. James Swisher), who was four miles away, called me trailing smoke, so I turned 030 degrees and instructed my wingmen to hit my mark with all they had. Later intelligence reports said they got secondary explosions.

I left the target without a lot of things working for me except the red and yellow lights on the instrument panel. I pulled the Rat on and noted the airspeed – 385 knots.

Jagged pieces of the canopy were still hanging to the front frame, and that got my attention pretty good because I figured the ejection system might have been hit also, so I would have to crawl over the side. Although I wasn’t ready to eject, I raised both armrests and the canopy frame blew off as advertised. I felt a little better.

The jungle was dense, but I still didn’t want to go out until the last minute for fear of being shot on the way down, or at least to lessen the chances of someone seeing my chute. A 1,000′ high karst appeared under my left nose so, I decided to punch out over it in hopes of landing on top, thinking the enemy wouldn’t be up there, and besides it would be a good place for a chopper to pick me up.

I was still ready to go over the side as I ran through the checklist: gun film in my G suit, visor down, chin strap fastened, head back, boots in the stirrups, pull both triggers. So, at about seven miles from the target, at 240K and 1,500′, I had a great rocket ride that took me up 150′ or whatever. The butt kicker worked, and I was in one of the greatest experiences of my life. All pilots should get to do that once a year instead of taking a stan/eval check.

The next thing was to pull the lanyard and drop the survival kit and dingy, so of course, the damn lanyard wouldn’t pull. I jerked it hard a couple of times and the handle came off in my hand. Go figure!

And worse, I missed the karst by a little because I couldn’t remember which risers to pull that would fly me to a landing on top (I never was very good with math). As it happened, the wind blew me over, and while I don’t remember my body hitting the bluff, the chute did, so it dragged for a while and then streamed. Now I was falling face down with mean-looking rocks and trees approaching at flank speed.

With a big limb, dead in my trajectory, I closed my eyes and wished I’d gone to church more, as my body bounced off of hard things for what seemed like an unfair length of time. Finally, all was quiet as I gently bounced up and down. My chute had caught on a low limb and when I opened my eyes, I was hanging about 18″ off the ground. I couldn’t believe it.

Everything had happened so fast that I wanted to just sit there for a minute and soak it in. None of my body parts were giving me major pain (they would later that night), but I was bleeding from my nose and head. (That’s the best way to get a Purple Heart.)

After a few minutes, I felt myself going into shock. Hot, clammy, apprehensive, shortness of breath, symptoms that I had learned at snake school in the Philippines. So, I climbed out of the harness, elevated my feet, closed my eyes, and thought about sitting on the bank of the Lampasas River in Texas with a bobber in the water, catching 5″ bluegills. It worked, and after maybe 30 minutes I was back again.

By this time, it was getting seriously dark, so I pulled the dingy about 50′ into some dense undergrowth, leaned it over a log and climbed under. I could hear dogs barking, and that wasn’t a good sign since the Pathet Lao didn’t take prisoners.

It was just cool and damp enough to keep me awake most of the night, and when I did doze off, the flights of three hero B-52s from Guam woke me up by spacing out 324 five hundred pounders all around me. I told them on guard channel to go play somewhere else, but they didn’t respond. I think they were listening to Bing Crosby sing Silent Night on AFN radio.

At 0800 the next morning, here came Lt. Swisher again. He had to give up the night before because of darkness, but was up at 0200 and out again at first light. Don’t you love a guy like that? Although I couldn’t see him, I could hear his putt-putt. He responded to my call and asked me to pop smoke, which I was reluctant to do, so I moved over to the bottom of the karst where there were large rocks.

When I spotted his plane, I told him to start a left turn and stay in it until I said stop. “Now look down your wing at a large pile of rocks. That’s me waving like a windmill.”

That was fun until he told me to hang tight, that he’d be back later. Well, I remember thinking I’d just as soon he’d hang around for a while, but before I could tell him, he was gone.

After about thirty-minutes there were so many aircraft in the sky it made me feel important. A Crown C-130 flying high and directing traffic, four Sandy prop jobs (one was Capt. James Jamerson, later four stars) flying low to keep the enemy heads down, a flight of Huns making tight circles at high speed, and two determined looking Jolly Green Giants coming in fast. It was just like in the movies.

The low chopper (the Candy Ann), flown by Lt. Lance Eagan (U.S. Coast Guard), asked me to move away from the karst so he would have more rotor clearance, so I went into the trees again.

After confirming that I was alright, a heavy jungle penetrator came crashing down bringing a lot of limbs and foliage with it. It took 240′ of cable, and I quickly unfolded two legs and strapped on. The ride up was slow enough for me to maneuver around some of the larger limbs, but I just crashed through the others because the cable was twisting and the chopper was moving.

It didn’t help my morale any when I looked up and saw the hoist operator (M/Sgt. Maples) with his hand on the emergency cable cutter; the “Guillotine.” But when I cleared the trees, he signaled the pilot, and we were up and away at flank speed.

When I got up to the door, the PJ, A1C Sully, jerked me in and yelled, “Quick, jump across the flak vests and get in the back.” On the way to Nakhon Phnom and after high-fives all around, I took inventory. I had lost my pistol and gun camera film in the trees, but I had my head, my arms, my legs, and memories of a bunch of great guys who knew how to make things work. It beat the hell out of walking home.

And would you believe it? The co-pilot of the high Jolly was taking color pictures while they were pulling me up through the trees. As it turned out, I was the 1,500th aircrew to be rescued by the ARS in SEA and the 331st by that unit. (See Daedalus flyer, Vol. IX, No. 3, September 1969, for the chopper pilot’s description and pictures of the rescue).

Because that mission was supposed to be my last, they had closed me out, so it took a call to Saigon to get one more. Who wants to be shot down on their last mission? The general said “OK, but keep him in-country.” Two days later I walked through my front door in Lubbock, Texas. My lovely wife and two daughters were grinning. It was Christmas Eve.

Addendum: I had been shot up a few months earlier, flamed out, and dead-sticked a D-model into the short runway at Bien Thuey in the Delta. After touching down at 205 knots, my hook grabbed the approach end anchor chain so I pulled that thing the wrong way. They said I stopped in 250′. The leg straps on my chute were pulled so tight I thought for a while I had been placed into a different social stratum. I’d always rather be lucky than good.

-Forrest Fenn