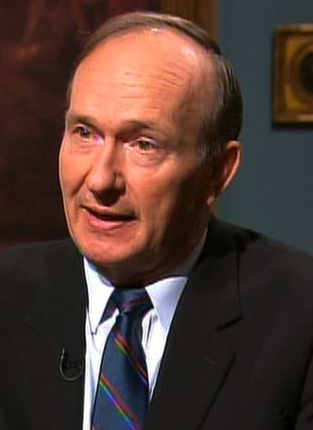

As a co-pilot of the two-seat F-100F, Gruters was shot down twice. The first shoot down required a parachute water landing less than 1 mile offshore near the North Vietnamese city of Đồng Hới while under fire from the North Vietnamese coastal guns in November 1967. While North Vietnamese boats were prevented from intercepting the downed pilots by strafing U.S. F-4 fighter-bombers, First Lieutenant Gruters and Captain Charles Neel were rescued under heavy fire by two USAF HH-3E Sea King helicopter crews based 60 miles (97 km) away.

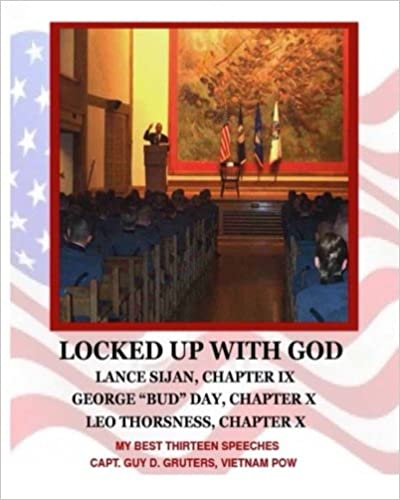

Gruters was shot down for the second time on December 20, 1967. He and fellow pilot, Colonel Robert R. Craner were captured and imprisoned in the Hỏa Lò Prison (Hanoi Hilton) among other camps. Upon their initial incarceration, Gruters and Craner cared for Lance Sijan before Sijan succumbed to wounds and torture in January 1968.[1]

Gruters spent 5 years and 3 months as a prisoner of war before his release in 1973. Guy Gruters’ testimony was instrumental in Lance Sijan receiving the Medal of Honor posthumously in 1976.

Guy Gruters’ story was described in the book, “Bury Us Upside Down”, “Into the Mouth of the Cat”, and “Misty: Fast FACS.”

Source: Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guy_Gruters#cite_note-Galdorisi-1)

A wealth of information on Guy’s extraordinary life can be found at his website https://www.guygruters.net/.

Hell on Earth

“Gruters flew more than 400 missions over North Vietnam before he was captured. At that moment, his world changed forever. He was taken to the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” and subjected to inhumane abuse that is almost beyond imagining. He shared a window-less cell with one other POW. They had no recreation time outside and were given two meals of bread and water a day.

“The bread was hard as a rock,” Gruters said. “It had weevils in it. It was full of rat excrement. You’re thirsty all the time with only two quarts of water a day, especially in the summer. You had devastating thirst. You’re hungry all of the time. You’ve got hunger pains until you lose 60, 70, 80 pounds.”

Many of his fellow POWs died of dysentery or were afflicted, as Gruters was, with various parasitic diseases. Then there was the mistreatment that he received from the guards. “The guards are constantly … trying to catch you doing something wrong, like communicating with the cell next door by tapping on the walls—which we did all the time,” Gruters said. “In which case, they were delighted because they could get you into the torture room for three days and three nights. Guards come into a communist prison camp as normal people like everybody here,” Gruters said as an aside. “Three months later, with that kind of power, they are cruel maniacs. Watch it if you ever get [to wield] power. It can really mess you up.” The torture rooms were just 10 feet from his cell. He always could hear his fellow POWs screaming in agony. He knew that it would eventually be his turn, too. And always, there was the hell of the forced inactivity and the loneliness of the camp. …As his friends were tortured and killed just feet away and he was unable to do anything to stop it, a maddening rage began to well up inside him that he said was the fruit of his pride.

“Great anger started to grow in me,” he said. “And I didn’t know enough to stop it. I had never been angry at anybody in my life, really. But now I’m really angry. And it developed into a terrible hatred.”, but this anger and hatred didn’t result in Gruters lashing out at his guards—an action that would have led to a slow and cruel death. Instead, he considered turning on himself. He was tempted to starve himself to death. That would be the way to beat his guards. They couldn’t get at him anymore if he was dead.

The Catholic faith that had been instilled him from childhood, however, kept him from giving into this temptation…“God converted my heart from total pride to being able to see through the pride and overcome the hatred and to start praying,” Gruters said. “Once that happened then there was the chance of living through the experience.”” Source: Excerpted from an article by – by Sean Gallagher, Criterion Online Edition