Three taps on the Shoulder, by Ralph Taylor

“So I spoke to the 4th TFW commander (a B/G) and he said that he knew where I was coming from, and that fighter jocks would be reluctant to admit those thoughts, but that he himself had entertained similar thoughts on occasion. He said that he would write a letter of recommendation for my removal from flying status at the convenience of the Government with no bias or stigma. He did just that, and I enjoyed a rather fabulous career for almost 29 years total without recriminations of any sort.”

“Here are ‘prequel’ tales about the three taps on the shoulder that began to tell me that flying that great stick of dynamite was more fun than you can have sitting down, but for some of us it was not conducive to a long life. As you know, the clinching fourth tap was that night ride in the Arizona desert in May of ’60.”

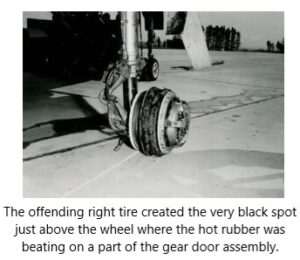

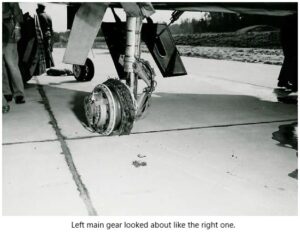

Firm Tap #1: This Tap occurred just 10 months after arriving at Hahn AB in Germany in January ’57 to check out in the F-100C…not a good experience for a newbie! I was flying wing on a live scramble (guns armed), and just before I broke ground, I felt the right tire blow. I had to go all the way to the ADIZ (Air Defense  Identification Zone) separating East and West Germany for a “No-Contact.” By the time we returned for landing, they had the fire trucks, ambulance and of course the chaplain all lined up and waiting for me to clobber. Just a short time before, a jock at Bitburg AB had landed a Hun with a blown tire and lost it off the runway, wiping out the gear and bending the plane pretty good.

Identification Zone) separating East and West Germany for a “No-Contact.” By the time we returned for landing, they had the fire trucks, ambulance and of course the chaplain all lined up and waiting for me to clobber. Just a short time before, a jock at Bitburg AB had landed a Hun with a blown tire and lost it off the runway, wiping out the gear and bending the plane pretty good.

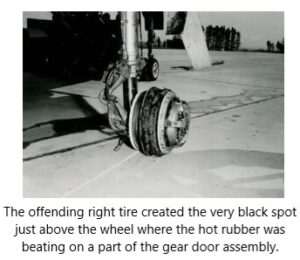

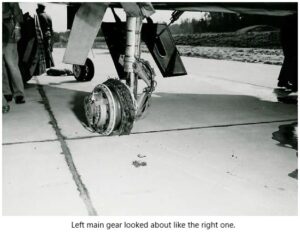

Of course, lead landed first in the event I closed the runway. I made one of the most careful landings I had ever made. As I flared, I tilted the bird so as to touch down first on the good left gear and held it there as long as I had airspeed. When the blown tire touched, I jumped on the brakes with the Antiskid turned off and deliberately blew the other tire. With equal resistance from both wheels, I rolled right down the centerline of the runway. As I was rolling, I knew if I stopped on the runway it would be closed for quite a while, so I just taxied off the runway to a stop. As it was, they still had to close the runway to sweep the rubber that I spread all over it.

I had thought of the technique of holding the blown tire off and intentionally blowing the good tire while contemplating my situation before we RTB’d (since it was a “lesson learned” from postmortems of the earlier similar incident at Bitburg). As you can see, I scratched up the concrete pretty good, but the left and right wheels were pretty equally ground down. I don’t think my wheels could be repaired. 🙂

I had thought of the technique of holding the blown tire off and intentionally blowing the good tire while contemplating my situation before we RTB’d (since it was a “lesson learned” from postmortems of the earlier similar incident at Bitburg). As you can see, I scratched up the concrete pretty good, but the left and right wheels were pretty equally ground down. I don’t think my wheels could be repaired. 🙂

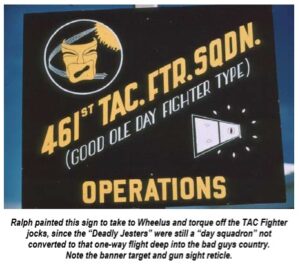

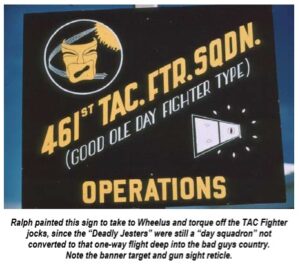

Even Firmer Tap #2: This incident occurred on a high-altitude gunnery mission at Wheelus AB, Libya, circa

1959. The night before, there was a big party at the Officer’s Club (which usually means, let’s all get drunk as a skunk). I elected to remain in my high-class tent with plywood sides and a couple of windows and write a letter to Jo or read a book (I continue to refrain from any alcoholic beverages and the use of profanity).

I was awakened by the drunks returning sometime after midnight, whereupon they decided to have another party right there. The next morning, we suited up for a gunnery sortie. I was in a flight with three hung-over drunks who had difficulty climbing the boarding ladder to breathe 100% oxygen in an attempt to return their brains to something like normal! I had made a couple of passes with no problems. On the third pass I was slightly out of position (which is not that unusual), so I honked back on the stick to catch up with the banner.

I was awakened by the drunks returning sometime after midnight, whereupon they decided to have another party right there. The next morning, we suited up for a gunnery sortie. I was in a flight with three hung-over drunks who had difficulty climbing the boarding ladder to breathe 100% oxygen in an attempt to return their brains to something like normal! I had made a couple of passes with no problems. On the third pass I was slightly out of position (which is not that unusual), so I honked back on the stick to catch up with the banner.

I was still lagging so I added a few more G’s (to about 7 or 8) and I blacked out (which again is not unusual at altitude and high G’s). I released the stick slightly and my vision did not return…I was blind as a bat! I instinctively went through the motions of rolling out of my turn while pulling up to avoid the weighted banner. I was helpless. The other members of the flight said that I started to babble about where I was, my attitude, and what I was doing, and telling everyone else what to do to avoid a midair (and they said that the strange part was that most of it made sense), but I have no memory of what occurred.

One of the wingmen recalled me saying that I was reducing throttle for a descent. I could just as easily have rolled over to an inverted position and pulled back on the stick, performing a Split S maneuver, but that may have resulted in a dive straight into the Mediterranean. My vision slowly returned. The first thing I saw on the altimeter was 12,500 feet, and I was in level flight. At about the same time, a flight member spotted me, joined, and we proceeded back to the base.

Of course, I had to loiter while the other three birds landed. While waiting to land, the squadron flight surgeon came on the radio and administered some silly tests to verify that I was capable of landing. I had to go through the same routine with the fire trucks, medics and chaplain lining up for a crash. My landing was perfect. It had to be with the audience that I had! When I taxied to my parking spot, there was an ambulance waiting to rush me to the hospital for a battery of tests. The flight surgeon was waiting and insisted on personally taking a blood sample from me as the first order of business. In a few minutes a medic walked up and told me that with my blood alcohol level I should be unconscious. After a few more frantic moments they determined that the Doc had used alcohol to swab my arm and had injected the stuff into my vein. The medic drew another blood sample, and it was normal. (The flight surgeon had attended the party too!!)

Maintenance determined that my oxygen regulator had failed with no warning, which put me up the proverbial creek without a paddle. Instead of me sucking the 100% oxygen that I had selected, I was getting only pressurized air, so I had hypoxia of the worst kind. It was ironic that this happened to me, because, in my annual altitude chamber flights, I always volunteered to remove my oxygen mask and “practice” hypoxia to demo its effects to others. Prior to mask removal, you were given a board with pegs inserted with the round end down and you were told to remove each peg, reverse the ends and place the pegs in the board with square holes.

After the mask was removed, I recalled doing a few properly, but then I didn’t really care and started throwing pegs all over the place prior to losing vision and consciousness. The chamber crew immediately reattached my mask, but I remembered the warning sensations very well—except at 30,000 feet in a fur-ball with a tow ship and a banner! (And like the later encounter with the Arizona desert, this misadventure could have been fatal.)

A Gentler/Sucker Tap #3 This tale stems from an exchange of war stories with Wally and a question about the cover photo on Intake Issue Two which showed a Myrtle Beach Hun taking to the air.

I arrived at Seymour in January ’60. I only passed over Myrtle Beach once and was too busy to see much of what was on the ground. They were closing the runway at Seymour for maintenance and our “go-to” destination was Brookley at Mobile, AL. Sixteen of us took off and made a low pass over Myrtle Beach as a diamond of diamonds, but since I was flying slot behind the squadron commander (and they often are the worst at leading such a gaggle!), I was very busy!

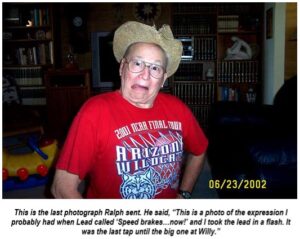

We then climbed to about Angels 30 and loosened up a bit. While still at altitude, lead told us to close it up as we approached Mobile (don’t ask me why!!) Lead began to descend and soon we were going too fast to be in so close. Someone keyed their mike and said, “How about speed brakes?” Lead uttered a selected word or two and then called, “Speed brakes…now!

For a moment, I thought the world had drastically slowed, and I went screaming ahead at warp speed. I will never know how I passed lead without hitting him since I had my bird up to where I had a good burble on the VS, but somehow I did.

The next thing I knew, I was WAY out front of the gaggle, and I took time to check my gauges. I cranked that hydraulic selector knob CW to the stop and saw that my hydraulic pressure was on ZERO. Of course, lead came on with a couple more selected words and asked me in a loud and higher-pitched voice, “Can’t you hear?” I very calmly told him that I had lost hydraulic pressure. He said, “Oh Poop!” or something like that! 🙂

The next thing I knew, I was WAY out front of the gaggle, and I took time to check my gauges. I cranked that hydraulic selector knob CW to the stop and saw that my hydraulic pressure was on ZERO. Of course, lead came on with a couple more selected words and asked me in a loud and higher-pitched voice, “Can’t you hear?” I very calmly told him that I had lost hydraulic pressure. He said, “Oh Poop!” or something like that! 🙂

The remaining flight members did a 15-ship flyby over Brookley and Mobile while I loitered. During that time the tower marshaled the entire disaster team…meat wagon, fire trucks, writers, photographers, looky-loos, and of course the ever-lovin’ chaplain.

I never again nursed brakes like I did that day. I used only one application and had just enough pressure to turn off the active without nose gear steering.”

As told in Issue #7 of The Intake, Summer 2008

Ralph C. Taylor, LtCol USAF, Ret., “Headed West” on January 26, 2008.

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph C. Taylor died suddenly and peacefully in the company of his wife, Jo on January 26, 2008. Ralph spent a 29 year career of honorable service in the U.S. Air Force, first as a pilot flying many aircraft including the F-100C, then in various missile programs including the Titan II Strategic Missile Program and the Range Safety Group at Cape Canaveral during the manned space program including the Apollo lunar missions.

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph C. Taylor died suddenly and peacefully in the company of his wife, Jo on January 26, 2008. Ralph spent a 29 year career of honorable service in the U.S. Air Force, first as a pilot flying many aircraft including the F-100C, then in various missile programs including the Titan II Strategic Missile Program and the Range Safety Group at Cape Canaveral during the manned space program including the Apollo lunar missions.

Ralph was born May 10, 1931 in Lexington, KY. He graduated from Henry Clay High School and attended the University of Kentucky in the College of Aeronautical Engineering. His military service began in the Aviation Cadet Program in December 1953, receiving his commission and Pilot Wings in March 1955. As if this were not enough excitement, on the 18th of this month he married the love of his life, Jo Riddell. Ralph’s final assignment was at Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, AZ where they retired in August 1982. Ralph and Jo have five children, Connie Miller (Tom), Cathy Vaughn, Conrad Spoke, Chuck Taylor (Karie), and Cherri Burd (Kelly). They also have nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, who all loved PaPa very much. A private family service was held. In lieu of flowers donations may be made to the Freedom From Religion Foundation, P.O. Box 750, Madison, WI 53701. Arrangements by BRING’S BROADWAY CHAPEL, 6910 E. Broadway.